Originally published in Liberation Newspaper, June 2015

Heroic rebellions led by Black youth in Ferguson and Baltimore have shown the power of one of the oldest weapons in the arsenal of the oppressed—the uprising. Movements for justice pursue many strategies and tactics and different moments, but the kind of righteous anger shown by the rebels fighting police brutality has time and time again been able to put the system on the defensive.

The struggle for LGBTQ liberation has made stunning advances in recent years, and the world is waiting for a historic ruling by the U.S. Supreme Court on the issue of marriage equality. The movement did not reach this point by the goodwill of politicians and judges. It is the product of nearly a half century of resistance and struggle, an era that began, as with Ferguson and Baltimore, with heated rebellions against the cops.

The 1969 rebellion against the police at the Stonewall Inn in New York’s Greenwich Village stands out as a landmark moment in the struggle for equality. But there were important uprisings that preceded Stonewall as well and set the stage for today’s movement.

Cooper’s Donut Fightback—Los Angeles

Trans workers have long faced regular brutality from the police, as well as discrimination in the labor force, health care, education and housing. Forced to live on the edge of society, trans people often gathered together at night in remote venues, away from the police and violent queer-bashers.

A major gathering spot for trans people in Los Angeles, for example, was Pershing Square Park in the city’s downtown area. In the late 1950s capitalist developers were working hard to push out the trans people who gathered nightly.

Nearby to Pershing Square, on Main Street, was Cooper’s Donuts, another busy hangout. One night in May, 1959, cops entered the place to hassle and arrest the trans people and others socializing inside. This time, the people fought back. As described on queerty.com:

“From the donut shop, everyone poured out. The crowd was fed up with the police harassment and on this night they fought back, hurling donuts, coffee cups and trash at the police. The police, facing this barrage of pastries and porcelain, fled into their car calling for backup. Soon, the street was bustling with disobedience. People spilled out in to the streets, dancing on cars, lighting fires…”

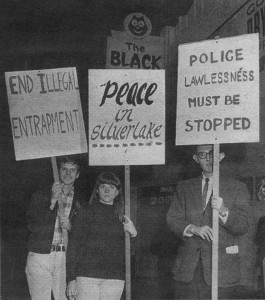

This and other uprisings in Los Angeles, such as the fight back against the police at the Black Cat Bar in Silverlake (1967), set a foundation of militancy for the movement that would explode in the following years.

Compton’s Cafeteria Uprising—San Francisco

While San Francisco has a “liberal” reputation with respect to sexual orientation, in reality the banning of any perceived LGBTQ person from public venues was common in the 1950s and 1960s. Some bars in San Francisco, like Barney’s Beanery, put up bigoted signs with slurs warning LGBTQ people to “Stay Out.” It was unlawful in the city to “cross dress” and “impersonate a female.”

The Tenderloin area of San Francisco, traditionally home to much of the city’s large trans community, was the scene of another major pre-Stonewall uprising that took place in the summer of 1966. As documented powerfully in the film “Screaming Queens,” when the restaurant management at the popular all-night venue Compton’s Cafeteria decided to kick out everybody and called the cops, trans residents rose up.

When the police stormed in, someone threw a cup of coffee at an officer and fighting broke out between the cops and 50 to 60 patrons. Unlike Stonewall and other pre-Stonewall rebellions, which were spontaneous uprisings, the struggle around Compton’s Cafeteria had the benefit of organizational leadership. The Vanguard group, a collective of young, militant trans people called a demonstration the next night at the cafeteria. Vanguard worked out of Glide Memorial United Methodist Church, a major supporter of trans youth. The demonstration drew hundreds of people, who physically fought back against the police, breaking windows and burning cars.

This rebellion sent shock waves through the city. Activists from the already established gay and lesbian groups called a solidarity rally the next day in support of the trans people who were beaten and arrested. Progressive forces rallied to demand, for the first time anywhere, programs to support trans youth, including job training, housing and access to trans-friendly healthcare.

Lessons for today’s struggle

The young warriors who fired the early shots in these historic uprisings, themselves learning from a previous generation, set the stage for a major expansion in LGTBQ rights. From scattered uprisings a movement was born that now involves millions of people who crave justice and equality. These uprisings were not just milestones for the LGBTQ community, but the struggles of the working class and all oppressed people. And just as trans people in downtown Los Angeles were targeted in 1959, today the same process is underway, as developers use police terror to drive homeless and other poor people out of the area to construct a new trendy “DTLA” area with outlandish high prices and amenities for the privileged. The 1959 rebellion against these forces can be tapped as a source of pride and power in today’s struggles.

The 1960s LGBTQ uprisings took place during a period of rising worldwide struggle against all forms of oppression, with fierce movements fighting against racism and sexism and the capitalist system itself. Solidarity and a common perspective of revolution and emancipation drove people into the movement from a variety of struggles. Today it remains essential to build that sort of principled unity across all boundaries, especially by working and fighting alongside one another in the streets.