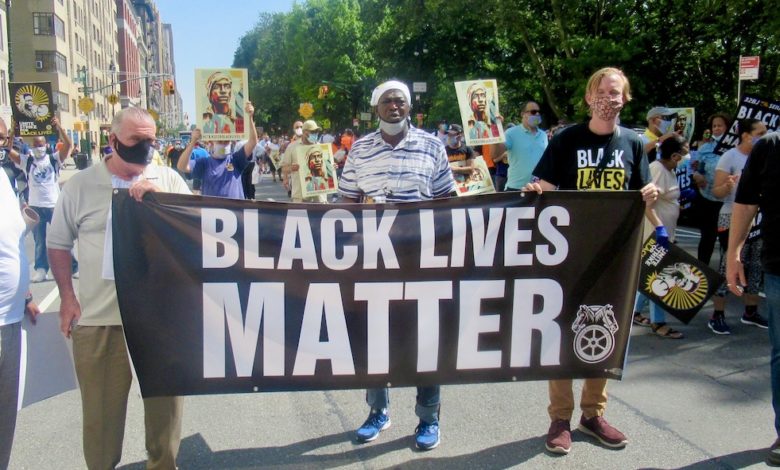

The national Movement for Black Lives took a big step forward on July 20 when the organized labor movement weighed in. Protests in as many as 100 cities that day rang out with a strong message that Black Lives Matter is a labor issue, an issue that affects the entire labor movement, and affects every individual worker. This is solidly in the labor union tradition of “An injury to one is an injury to all.”

Sponsors of the national protests include the SEIU, the International Brotherhood of Teamsters, the United Food and Commercial Workers, the National Domestic Workers Alliance, the Communication Workers of America, the United Farm Workers, the United Federation of Teachers, the Amalgamated Transit Union and a host of community groups.

Mary Kay Henry, president of the Service Employees International Union — which represents nearly 2 million members in the public sector, health care and property services–explained that essential workers were inspired by the Movement for Black Lives in response to George Floyd’s death, and sought to unite the fights for racial and economic justice.

The Teamsters union made the case for labor: “Today workers with the International Brotherhood of Teamsters joined other major national labor organizations, leading racial and social justice groups, and activists in the national Strike for Black Lives. Hundreds of Teamsters across sectors held protests in 15 cities across the U.S., joined by thousands more who walked off of their jobs for eight minutes and 46 seconds in honor of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and so many other Black people who are victims of police violence.”

Teamsters joined the national movement in confronting systemic racism, demanding solutions from government and corporations that center communities of color and dismantle racist policies.

“The International Brotherhood of Teamsters was founded on the principle of winning justice for all workers, and that cannot happen unless we dismantle racism and racist systems that continue to hold Black workers back,” said Marcus King of the Teamsters.

Strike for Black Lives organizers called on businesses to “dismantle racism, white supremacy, and economic exploitation” and ensure access to union organizing. The protests also demanded that Congress pass legislation for personal protective equipment, essential pay increases and extended unemployment benefits.

Organizers encouraged people unable to leave their jobs to kneel or stop work for 8 minutes and 46 seconds, the amount of time that a Minneapolis police officer knelt on the neck of George Floyd, whose murder sparked a world-wide movement for Black lives.

Some highlights from around the country

New York. In Manhattan, more than 150 union workers rallied outside Trump International Hotel, holding signs that read, “Black Lives Matter,” “Racism is a public health crisis” and “Unions for all.” “Until we have racial justice, we cannot have economic, climate or immigrant justice” stated Kyle Bragg, the President of 32BJ, the Service Employees International Union (SEIU), which spearheaded the protest. Members of National Nurses United carried a banner reading, “Racism is a public health crisis.”

Chicago. Fast food workers, transit workers and healthcare workers marched through downtown Chicago, followed by a long car caravan. The march stopped at a local McDonald’s, where the workers there discussed defunding the police and the need for unions in the workplace. Leshia Townsent, a Fight for $15 leader, exclaimed that she “had to go on strike at McDonald’s just to get masks and protective equipment.”

Boston. Essential workers in Massachusetts walked off the job Monday as part of nationwide events to protest systemic racism and economic inequality that has worsened during the coronavirus pandemic. The strikers held a rally at the State House in Boston.

Seattle. About 250 youth came to a protest in Occidental Square Park and marched to City Hall. They demanded imprisoned protesters be freed and their records cleared; to convert a police precinct into a youth center and to stop the police sweep of homeless encampments. Proteseors also expressed solidarity with the Duwamish tribe, demanding that the city acknowledge stolen land. The city was named for the Duwamish leader Chief Seattle, but the tribe has yet to be justly compensated for their land, resources and livelihood.

San Francisco. Organizers estimated that about 1,500 custodians walked off their jobs and later marched to City Hall, banging drums and hoisting banners proclaiming, “Justice for Janitors,” “Share the prosperity” and “Essential workers for Black Lives Matter.” Several signs read, “SEIU: You shouldn’t have to die to feed your family.”

Los Angeles. A caravan of several hundred cars and trucks drove through South Los Angeles with “Strike for Black Lives” signs in English and Spanish on their windows. The Los Angeles protesters converged at a McDonald’s on Crenshaw Boulevard, where they blocked the driveway for eight minutes and 46 seconds in remembrance of the police murder of George Floyd.

Hattiesburg, MS. Workers protested outside the Maximus Call Center in solidarity with the national strike. Tiandra Robinson, a campaign organizer, explained: “Racial equality and social equality and labor equality are all intertwined. You cannot have one without the other.” After a two-year struggle over wages, the workers at the center still make only $11.54 an hour.

Detroit. SEIU Healthcare Michigan organized a walkout from six nursing homes, demanding much-needed PPE, more paid sick days, fair pay and free testing for COVID-19. Passing cars overwhelmingly showed their solidarity by honking their horns or shouted support.

Fighting racism is the task of all workers

Systemic poverty affects 140 million people in the U.S, with 62 million people working for less than a living wage, according to the Poor People’s Campaign: A National Call for Moral Revival, a strike partnering organization. An estimated 54 percent of Black workers and 63% of Latino workers fall into that category, compared to 37 percent of white workers and 40 percent of Asian American workers, the group said.

Justice Favor, 38, an organizer with the Laborers’ International Union Local 79, which represents 10,000 predominately Black and Latino construction workers in New York City, said he hopes that the strike motivates more white workers to acknowledge the existence of racism and discrimination in the workplace.

“There was a time when the Irish and Italians were a subjugated people, too,” said Favor.. “How would you feel if you weren’t able to fully assimilate into society? Once you have an open mind, you have to call out your coworkers who are doing wrong to others.”

From Chicago, Catherine Henchek, an unemployed worker and member of Parents 4 Teachers, which supports the Chicago Teachers Union, summed it all up. “It’s vital for the union movement to support Black Lives Matter. Workers of all races are being oppressed by the capitalist class. The COVID-19 crisis has shown us who the essential workers are and they are not the bosses. Yet Black workers face the additional burden of racism. We must not allow the capitalist class to divide us by race. “

Henchek who is also an organizer for the Party for Socialism and Liberation, concluded, “We all have a stake in fighting racism and uniting the working class. Unions are becoming stronger and must use that strength to fight for the rights of all workers, especially the most oppressed. When we fight together we win.”