The prison industrial complex intrudes upon the lives of millions of people living in the United States. It places an ever-tightening noose around the necks of those who are incarcerated as well as their family members.

In the United States, we are indoctrinated into believing prisons are necessary to maintain order in society. As a result, federal, state and city governments spend $81 billion a year in taxpayer’s dollars to incarcerate over 2.4 million people in prisons and jails. We are told the $81 billion covers the cost of running the corrections system –prisons, jails, parole, and probation. The real cost, however, runs much deeper.

Who really pays the price of incarceration? Working class and oppressed people. Family members of the men, women, and children incarcerated in jails and prisons, both at the state and federal level, pay the cost of incarceration under capitalism, while their loved ones are legally enslaved due to the 13th amendment.

The insidious way in which the costs of incarceration are placed upon the shoulders of working class and oppressed people, and the impact mass incarceration has on the families and communities from which adults and youth are stolen and jailed, is rarely quantified and discussed. They pay endless policing, court and other legal fees. They pay to support someone in prison. They pay costs that extend far beyond the sentences being served, and continue long after an incarcerated person is released.

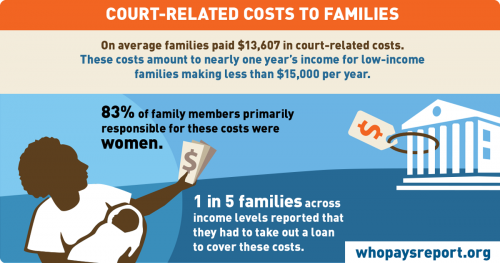

Many of these families are often already living in poverty, or one paycheck away from it. Exorbitant prison expenses push them further into debt. Research reveals the cost of supporting a loved one in prison can amount to one year’s total household income for many people.

Families and whole communities are punished, driven into debt

According to the findings presented by the Ella Baker Center for Human Rights, Forward Together, and Research Actions, a research team that worked with 20 community organizations to gather data on the impact of mass incarceration, more than half of the families directly affected by mass incarceration cannot afford the costs associated with conviction. Many of these families find themselves choosing between supporting their incarcerated loved ones and meeting their own basic needs such as buying groceries and paying rent.

By making prisoner’s loved ones bear the financial burden for incarceration, the prison-industrial complex punishes whole families and communities, who have committed no crime by anyone’s standards. The result is a legacy of collateral damage–poverty and trauma that continue throughout generations. This is felt most deeply by Black and Latina women living in or close to poverty, who are trying to keep their families and relationships intact.

In addition to money paid, long term costs to families include the criminal lack of mental and physical health care and support, the loss of children who are sent to live in foster care or with extended family members, permanent loss of income and/or decline in income due to the circumstances, and loss of opportunities such as educational and employment for the person incarcerated as well as their family members, due to the stigma that comes with mass incarceration.

What are they paying for?

Before the defendant even sets foot in a courtroom their families have often accrued thousands of dollars in fees and fines. This is the case whether the representing attorney is private or public. Though public defenders are free, there is an application fee attached to this service. Then there is bail or bond, and even fees for prisoner transport services, which average $1.00 a mile, with some companies adding a fuel surcharge.

If there is a conviction, there are mandatory surcharges for every convicted defendant, and also town and village court fees, DNA databank usage costs, and restitution paid to victims of violent attacks (even when the defendant is a child). For defendants who receive no jail or prison time, or are sentenced to less than 60 days, fees and surcharges must be paid within 60 days. For defendants imprisoned for a longer period, any money sent to the prisoner by family and friends will be taken by the correctional facility and applied to the legal balance.

Prisoner families subsidize the prisons and jails

In 2013 alone $460 million in concession fees was paid to jails and prisons, according to the Federal Communications Commission. These fees, the FCC says, “have caused inmates and their friends and families to subsidize everything from inmate welfare to salaries and benefits, states’ general revenue funds and personnel training.”

Fees are also charged by the for-profit corporations that manage prisoner’s expense accounts. For example, JPay charges incarcerated people at Auburn Maximum Security Correctional Facility in New York State a service fee based on the amount of money being deposited each time a deposit is made.

Even charged for room and board

While the government and big private corporations claim that the $81 billion covers food, board and facilities, many incarcerated and formerly incarcerated people report that very little money is spent on these basic necessities. They report inhumane conditions behind the walls, a criminal lack of rehabilitation and education programs, and gravely unhealthy food options.

More and more correctional services are managed by for-profit companies. With a captive audience, the tendency of these companies is to increase profit margins by providing fewer and declining services, and to pass costs onto prisoners and especially their families. Everything from the cost of room, board and medical treatment, most clothing and personal items, even food, is passed on to the prisoners, who may have no source of income, or earn pennies an hour. So it is the families who pick up the tab.

The government doesn’t mind, as kickbacks, known as “commissions” are provided by the private companies to the state and local prison system in exchange for exclusive contracts at facilities. Companies that provide phone service to prisoners, for example, compete with each other for contracts, not based on price or service quality, but on the size of the ‘commission’ they kick back to the prison system.

In 2015, the Brennan Center for Justice at the New York University School of Law found that policies allowing inmates to be charged for room and board exist in at least 43 states. In 2014, an appellate court ruled that Johnnie Melton, a Chicago inmate, would have to pay close to $20,000 to the Illinois Department of Corrections for the cost of his incarceration. Men and women in Florida have been charged $50.00 per day to be imprisoned and upon release have seen bills for over $50,000.

Medical care is not free

Medical care behind the walls is notoriously bad, and poor conditions in the jails and prisons often contribute to illness. In 35 states, however, incarcerated people are expected to pay for medical services and/or pay medical co-pays.

Unpaid medical expenses follow the inmate once the sentence is completed. If a released person owes $5,000 in medical expenses, they might be able to fight it “if you have a very good lawyer,” said Brooke Eisen of the Brennan Center. If ignored, the unpaid bill could lead to an arrest warrant. The state could cite the unpaid debt to block access to accessing public housing, to revoke one’s driver’s license, or lay claim to one’s estate upon death.

Unpaid medical bill from prison may also affect one’s ability to receive government benefits like Social Security.

Food as a luxury item

Food is another item treated as a luxury that families must provide. Incarcerated people report that prison and jail food is inedible. Many rely on snacks they buy at the commissary, or the processed snacks and food products they are allowed to receive from family and friends who mail or hand deliver them to the prison. At Auburn, a maximum security state facility in New York State, families are limited to sending or bringing 35 lbs. of food per month.

There are detailed descriptions on the food that can be sent, and how it must be sealed. Families are burdened with the cost of the food, plus at least $25 in USPS shipping costs. As a form of harassment, corrections officers often deny some of the food items, or claim the food or other packages are over the allowed weight, even when they are not. When this happens, family members have 14 days to come to the facility and pick up the item or it will be shipped back to sender with the fees taken out of the prisoner’s account.

Prisoners are clothed by their families

The prison only provides jumpsuits to entering inmates. Family members must buy everything else. Each facility has different rules for the number of items allowed, the number of pockets garments can have, the color of garments, and even the color of the stitching used in the clothes.

At Auburn, families must send or bring only brand new items. They are responsible for providing socks, pocketless polo shirts, t-shirts, shorts, sweatpants, pajamas, winter coats, jackets, raincoats, hats, gloves and other outerwear, sneakers, shoes for court appearances, and boots in winter, toothbrushes, lotion, mouthwash, hair products, towels, wash cloths and blankets.

The prison has very strict guidelines. Mouthwash can’t contain alcohol or be in a bottle larger than 16 oz., towels and washcloths have to be a specific size, material and color. Blankets must be fire retardant and cannot contain feathers. Shoes and sneakers must cost a certain amount of money and can only be bought in specific colors.

Guards change guidelines at whim

Corrections officers working the mail room on visit days can change these guidelines at whim. This keeps families in a heightened state of stress as they worry about whether or not their items will be approved. Oftentimes the footwear is not accepted by guards claiming there are small pieces of metal in the shoe, the color is slightly similar to one of the banned colors, or something preposterous such as pockets in the shoe that only corrections officers can see. This forces family members to either return the shoes and begin a new search for a different pair, or take them to a shoe shop and pay to have ‘pockets’ sewn up or have metal removed from inside the soles of boots.

Families face battles and obstacles at every turn. Things most people take for granted, like being able to pick up a phone and talk to family members whenever we’re moved to do so, grabbing a pack of underwear off a shelf at a store without giving a second thought to the color scheme, picking out a t-shirt without questioning whether you will be stopped at the gates because it is a v-neck instead of a crew neck, come at a very large financial and emotional price for those caring for people who are imprisoned.

Chris Ferguson, mother of to a 26-year-old African-American man wrongfully incarcerated in Auburn, reports making multiple trips to stores throughout New York City to obtain underwear, t-shirts, socks, and toiletries that meet Auburn guidelines. Chris works a 40+ hour work week and cares on her own for her 15-year-old son, her elderly mother, and a daughter with a serious mental illness.

“I work five days a week until 5:30 sometimes 6:30pm,” she said. “Then all the stores are about to close so I have to rush all around the city trying to find the things my son needs for a price I can afford. Then they have to be a certain color and material, it’s like come on now. By the time I get home I’m like so tired. We sometimes don’t have food in the fridge and I can’t even afford to buy dinner for the rest of the family. It’s hard you know?”

Chris, like many others in her position, labors physically and emotionally day in and out, caring for loved ones while simultaneously fighting for liberation and being made to pay for her son’s incarceration, financially and emotionally.

‘Profiting off the vulnerable’

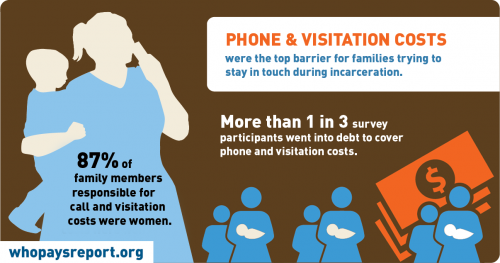

It is well documented that prisoners who maintain ties with their families, friends, and partners have a much lower recidivism rate than those who do not, and fare slightly better while incarcerated. Yet the prison-industrial complex places every obstacle in the way of this communication. The cost of maintaining contact alone can force mothers and partners to choose between paying bills and speaking to their loved ones.

The prison phone system is a $1.2 billion dollar industry dominated in all 50 states by a few private companies providing service. In exchange for exclusive contracts at facilities, they pay “commissions” to state and local prison systems. The companies compete, not based on price or service quality, but on the size of the commission.

These private companies set rates far higher than those of commercial providers, and charge fees for everything. Securus, which has contracts with over 2,600 correctional facilities, charges fees for establishing, maintaining, and closing an account. This is in addition to fees associated with placing call, and then during the call, based on the number of minutes the call lasts.

These fees make up about 40 percent of the average prison phone bill according to the Prison Policy Initiative. They contribute to driving the cost of phone calls, up to $1.22 per minute in some states, while the commercial rate is 4 cents a minute.

Prisoner advocates say capping calls at 7 cents a minute, just 3 cents more than commercial phone companies, would still allow phone companies to make a profit. It would also create more opportunities for families to communicate, but providers are having none of it. In 2014 prisoner advocates forced the Federal Communications Commission to cap the cost of interstate calls to and from prisons at .25 cents. Securus and Global Tel-Link responded by increasing fees on calls made to and from the prison which account for 90 percent of prison and jail calls.

Kasie Campbell lives paycheck-to-paycheck because she spends $150 a month on phone calls to her husband who is locked up in Texas for robbery. “The cost determines when I can talk to my husband and when my son can read a book to him. Its detrimental to rehabilitation,” she explained. “This is “profiting off of people in vulnerable situations.”

Joymara Coleman, a 25-year-old California college student, met her father for the first-time in 2014 at the Louisiana penitentiary where he is serving a life sentence. Nine months later, she said the prohibitive cost of phone calls meant that she had talked to him only twice since her visit.

The high costs of maintaining contact with incarcerated family members alone led more than 1-in-3 families into debt to pay for calls and visits. Family members who are unable to visit or talk with their incarcerated loved ones reported experiencing both a strain on the relationship as well as negative health impacts on family members.

The prison visit: Degradation and more money

Visiting prisons and jails presents another financial challenge. Often the families of incarcerated people do not own a car. Greyhound and Amtrak will only take you so far when your destination is a maximum security prison in a rural area hundreds of miles from your home. To go to Auburn Correctional Facility from New York City one has to travel via Amtrak or Greyhound to Syracuse, New York, which is about an hour away from the facility. A taxi from the bus/train depot to the prison can cost $50 or more.

One silver lining for families who can afford it is a van run by companies like Kismet Service, that run out of Black and Brown communities across New York City, and charges a flat rate of $55 roundtrip to transport families to five different prisons in upstate New York. These vans depart at midnight-to-2 am to get people to their facilities in time for a morning visit. It is because of companies like Kismet, owned by people from working class communities, that many families such as Chris Ferguson’s are able to visit their loved ones.

To most families, the financial burden is unbearable. However, it is nothing compared to the dehumanization process one must go through just to see a loved one behind bars.

In order to visit, one must submit to a series of demeaning searches. You must place all of your items in a locker, fill out paperwork, have your picture taken, sign a behavior agreement, remove your shoes, open your mouth, go through a metal detector, then be wanded by a hand-held metal detector, in some instances. In others, if the guards feel like it, they will search you by hand. Your hand is stamped with ink only visible under black light, and you are locked in a small cage located between the entrance and the visit floor for a few seconds.

Once released, corrections officers surround you while you wait in line to be beckoned over to a desk by an officer who then tells you where to sit. After you have your table and seat, you are then responsible with providing your loved one with lunch, as they have to choose between visiting with you or eating lunch in the prison cafeteria. The overpriced vending machines contain the worst of the processed foods. There are no vegetable options. A simple cup of noodles that would cost 89 cents at your local supermarket costs $2.50. Two small breaded chicken breasts costs $4.00. A small bag of 59 cent chips costs $1.50. Feeding just your loved one can cost at least $15.00 if you want to make sure they leave you with a full stomach.

If you want to take a picture with your loved one it will cost you $2.00 per picture. If you would like to play a game of cards during your visit you will be charged $3.00 for one standard pack of cards at the vending machines.

The visit lasts anywhere from 1.5-4 hours. Despite having a peaceful visit, officers will still terminate it early, regardless of how far you traveled to get there. It can get worse. In Arizona, family members and friends can be charged $25.00 just to visit!

‘I’m going home,’ they thought

In New York City, the majority of Black and Latino people incarcerated come from low income backgrounds and many live in government-subsidized public housing. Men and women just released from prisons and jails who previously lived in public housing often find they have no place to live. A Class B misdemeanor conviction, like possession of graffiti instruments or less than an ounce of marijuana, means you cannot live in a New York City Housing Authority apartment for at least 3 years after you finish your sentence.

A condition for parole is having a place to live. Not having a place to live means one can be sent back to prison for parole violation. If families in public housing shelter their loved ones to keep them out of prison they risk losing their lease risking displacement for the entire family.

No jobs upon release

Mass incarceration in America is tied to social control and profit, not to rehabilitation. Private corporations make money off those the government has deemed “illegitimate” and “criminal” often due to crimes of poverty and survival. Instead of providing opportunities for these people to work, the system stalks, captures, and imprisons them. Once behind bars, they are forced to labor for little-to-no pay. In many cases, while behind bars inmates work at jobs that were unavailable to them prior to their arrest, such as the men who were made to fight a series of wildfires in California as prisoners for $1.00 a day, saving the state thousands by not having to pay actual firefighters.

When incarcerated people are released, their criminal record makes it very difficult to find meaningful work, even at the jobs they worked in jail for practically nothing. Families support their loved ones even after they have done their time, as they search for a job. This includes paying for clothing, food, and transportation, for any social activities, for a bottle of water on a hot day.

Families shoulder these new financial and housing burdens after they have already spent thousands and thousands of dollars supporting their loved one while in prison. When they are unable to make ends meet, the cycle rears its ugly head once more placing everyone at risk for homelessness, hunger, or imprisonment; everyone except the real criminals, the capitalists perpetuating this cycle for profit.

Then there are the parentless children.

Some 1.2 million incarcerated people are parents to a young person under the age of 18. More than two thirds of these parents are serving time for nonviolent crimes. A report from the Bureau of Justice Statistics found that the number of incarcerated parents in state and federal prisons increased by 79 percent between 1991 and midyear of 2007. So many children in the U.S. have incarcerated parents that Sesame Street has updated its character list to include a puppet named Alex, whose father is incarcerated!

About 52 percent of mothers and 54 percent of fathers in state prisons, reported they were the primary provider for their children before incarceration. These numbers suggest that many more people are headed for the prison industrial complex as young children are left to fend for themselves in this unforgiving capitalist economy.

Children of African American descent are at constant risk of losing a parent on any given day as Black men and women are the most hunted, convicted, and enslaved populations.

For children with parents from another country, two convictions for jumping a turnstile in the subway will make a green card holder deportable.

The destruction of the family for Black and Latino people is a constant threat in the U.S.

Physical and mental toll

The stress on the immediate family often leads to, or exacerbates, physical and mental illness. Chris Ferguson, whose son is incarcerated at Auburn, suffered a burst appendix during his trial after the judge removed his private lawyer. She was hospitalized for three weeks. While this procedure doesn’t usually carry such a long hospital stay, the stress of trial, the destruction of her family by the incarceration of her son, and the resulting deterioration of her daughter’s mental health, had almost grave consequences for her.

Revolutionary spirit and will to fight will not be strangled

While well now, Chris is still paying for that hospital stay. She was forced to take out loans from her 401k just to make ends meet. She is at risk for losing her New York City Housing Authority apartment, as she is behind on rent and other bills due to her son’s legal fees and the cost of maintaining him in prison. Chris’ daughter, diagnosed with schizoaffective disorder, has also suffered monumentally since the capture and conviction of her brother. Her mental health has steadily deteriorated, leaving her and her family at a loss for how to support her.

Chris’s family is not unique. Millions of families are paying the price of incarceration in a plethora of ways. Poor and working class communities across the country are stalked by police, who arrest and lock up youth for petty offenses or crimes of poverty. Families of prisoners, 80% of whom are low income, are made to pay for this incarceration and its aftermath in hundreds of ways. The Criminal ‘Justice’ System unleashes upon this highly vulnerable of populations the most predatory of corporations, determined to squeeze every penny out of poor people, merely to have contact with their incarcerated loved ones. The resulting financial, health and social strains on all involved have life-long consequences, tear families apart, and deepen the poverty which then perpetuates the cycle of incarceration.

The financial hardships, emotional turmoil, housing difficulties, impossibility of finding a job after being released and more, lend themselves to the destruction of families, especially the Black family. It is no wonder that many of these families said they feel like they have a hangman’s noose around their necks, and the noose is tightening.

But even though the prison industrial complex may cause these families to carry what feels like an unbearable burden, it cannot and will not tie a noose around their revolutionary spirit and will to fight for their liberation. Families such as Chris’s have been fighting against the symptoms of capitalism such as police brutality, housing violence, health crises, and mass incarceration, to say the least, since their coming of age as people of color in the U.S. Even as the noose tightens and they feel themselves struggling to breathe, it is not enough to contain their will to to continue that fight.

Prison system exposes predatory nature of capitalism

This daily and minute-by-minute violence against working class people reveals the predatory nature of the capitalist system. As long as this system in place, exploitation and profit will trump rehabilitation. Loved ones who labor tirelessly to keep their families together will continue to face debt, homelessness, lack of opportunities, and stigmatization.

The only way to liberate our families and loved ones from the prison-industrial complex is to fight for socialism. This system values humans over profit, and would use this country’s vast wealth to meet people’s fundamental needs and eliminate the unemployment and poverty that leads to crimes of poverty and survival. Then, if and when people commit acts of aggression, they would have opportunities to be rehabilitated and healed instead of being further ridiculed, abused, and pushed into being violent.

Everyday working class people need to fight for a socialist revolution in the United States. It’s the only way to remove the noose of capitalism tightening round our necks, before we can no longer breathe.