The Hobby Lobby and Harris rulings handed down on June 30th are clear reminders of the reactionary times in which we live. They also remind us why the issue of selecting Supreme Court justices is the Hindenburg Line of the “lesser of two evils” argument in politics. If the lackluster performance of liberals and Democrats more broadly while in power often makes such arguments unpersuasive, then the ability of the White House to pick, and the Senate to confirm members of the judiciary (who make momentous decisions of everyday importance like these,) often is.

It is worthwhile to note, then, that the rulings on the June 30 actually reveal to us how hollow such an argument can be. As it’s reported in the media both rulings split on “ideological” lines with the liberals voting for the white hat and the conservatives for the black. While superficially true this ignores some key facts. Most crucially the enabling role of the Democrats, in particular Joe Biden, in putting some of our most conservative justices on the bench. Both Justice’s Scalia and Kennedy for instance were confirmed by Democratic-majority Senate’s by unanimous (!) votes. Unanimous.

Another of the hard right-wing, Clarence Thomas was put over the top by the 11 Democrats who voted in his favor. It is also worth noting it was current Vice President Biden who ran damage control for Thomas by limiting the scope of the Anita Hill allegations.

For those who swear by the “lesser of two evils” now is the time to launch a rebuttal consisting of a string of hypotheticals: “What if Mondale or Dukakis was the President;” “If only Democrats controlled both Houses and the White House.” The fact still remains that two of the most odious Justices on the Court and the conservative swing vote could have been stopped by Democrats, and were not.

This raises a key political issue: representation. Democrats have always been a “party of big business.” That being said, the Civil Rights and “Black Power” upsurges put the party in something of a bind in terms of its “base.” The solution during the 1970s was to create certain institutional mechanisms making the Democrats to a degree subject to demands from organized labor and civil rights groups.

This created a serious issue as it hobbled the party with the baggage of social democracy at the time where in the entire developed world the class imperative of capitalists was demanding a frontal assault on the rights of working people to restore profitability and stable rule of the “1%” (if you will).

This is why after a decade of this lash-up, Democrats jettisoned institutional power for “special interests,” (that is Black people and unions), and re-embraced business in general, the rising tech sector in particular, and becoming—in an increasingly vocal way—critics of the underlying premises of both the New Deal and Great Society.

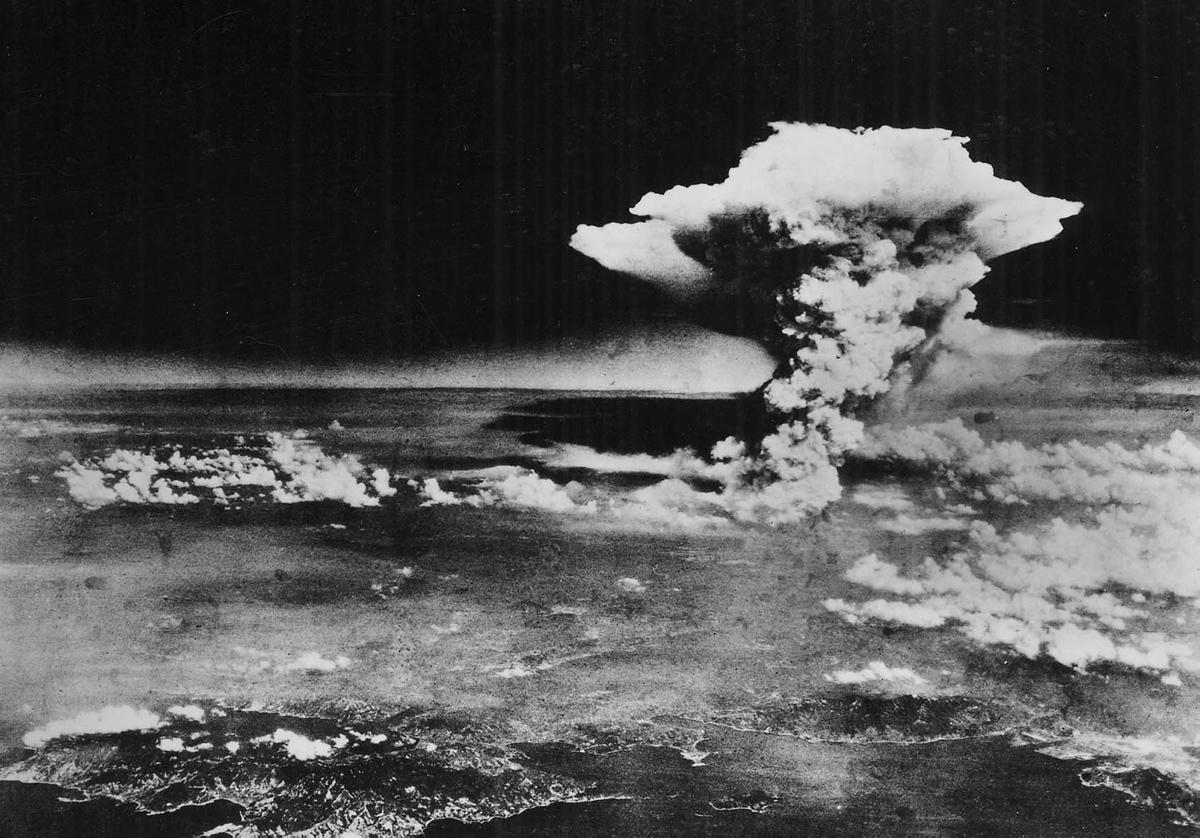

Herein lies the representational crux of the matter. The Tea Party is able to be most effective through a fundamentalist approach to things. It works because in a capitalist system, the scales are weighted more heavily towards pro-capitalist policies, policies that unleash the terrors of the “free market” more aggressively. So by acting in lock-step around far-right positions all of politics is pulled right-ward, which might not always be desirable for the capitalist class writ large, but that with reasonable checks is certainly beneficial.

For the Congressional Progressive Caucus the reverse is true. To aggressively advocate more progressive positions would mean attempting to seriously limit the military-industrial complex and war mongering urges so prevalent. It would mean more regulation of monopoly capital and more aggressive spending (with the requisite taxation) on the priorities of the poor, not to mention strengthening of the right to organize on the job. These are clearly not things on the wish list of the campaign donors who call the tune.

So to have any level of effectiveness within the Democratic Party, compromise on basic principles is a constant for these progressives, in exchange for the occasional crumb to ensure their appeals to voters are not entirely bankrupt. Anything more aggressive threatens the image of the Democrats as a “reliable” capitalist party to people who care about such things.

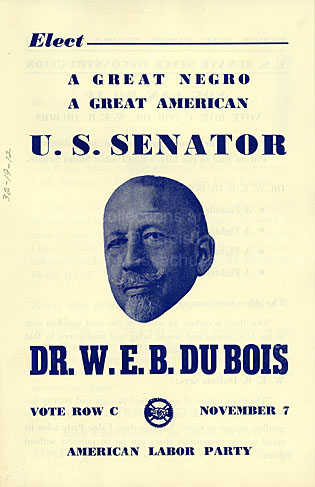

While one could take many lessons from this observation, the key one is that representation, for the exploited and oppressed, must be independent of the two major parties. It must exist in a space where it is both accountable to and in service of the interests, principles, and goals of those it represents. Relying on those whose core interests, and survival, rest on the forces most opposed to upward movement from the masses is no strategy for victory, only lesser and greater defeats.