It was the fourth anniversary of the Stonewall rebellion–June 24, 1973– signaling a new era for LGBTQ people. New organizations and formations were cropping up in cities across the country, including in New Orleans. Members of this new movement began to aspire to live in a new world without the the violence and oppression of anti-LGBTQ bigotry. For that reason they gathered at the UpStairs Lounge on that night in celebration and in worship.

It was the fourth anniversary of the Stonewall rebellion–June 24, 1973– signaling a new era for LGBTQ people. New organizations and formations were cropping up in cities across the country, including in New Orleans. Members of this new movement began to aspire to live in a new world without the the violence and oppression of anti-LGBTQ bigotry. For that reason they gathered at the UpStairs Lounge on that night in celebration and in worship.

However, murderous forces took the opportunity to carry out a deadly attack. The UpStairs Lounge was a bar, but on this occasion members of the Metropolitan Community Church (MCC) were also meeting there in the back auditorium holding a church service of their newly formed religious organization that had a special affirming ministry for LGBTQ people since the creation of the denomination in Los Angeles in late 1968 by Rev. Troy Perry.

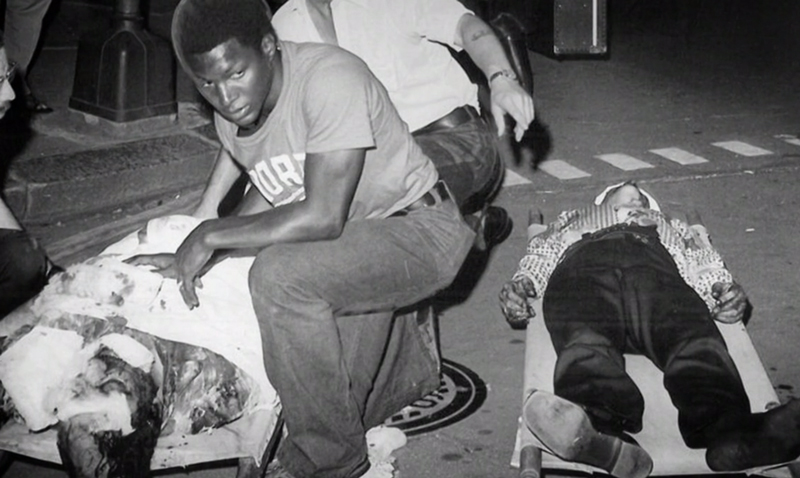

Thirty-two people died in the arson fire and more than a dozen were injured. Survivors said that there was the smell of gasoline before a swirl of flames engulfed the bar located on Iberville and Rue de Chartres in the French Quarter of New Orleans, La.

It was the deadliest fire in New Orleans history and certainly the deadliest attack in LGBTQ history. [Following the publication of this article, in June 2016, a mass shooting took place at the Pulse nightclub in Orlando, Fla., which is now the deadliest attack in LGBTQ history.]

“I was panicked about jumping, but two guys urged me to jump and I was small enough…Some big guy on the ground caught me, and I kept looking back but my friend never got out,” Adolph Medina of San Antonio, Tx, told the Associated Press of the flash fire that lasted less than 20 minutes and his efforts to escape it.

The Times Picayune carried an article on the arson fire featuring a picture of the charred remains of Rev. Bill Larson of the Metropolitan Community Church who could not escape through the window due to the metal bars that covered it. A third of those who died were members of the MCC congregation. The police did not bother to identify many of the victims of the arson attack.

“We don’t even know these papers belonged to the people we found them on. Some thieves hung out there, and you know this was a queer bar,” said bigoted Major Henry Morris, chief detective of the New Orleans Police Department.

Aftermath and the community challenge to bigotry

The police chose not to thoroughly investigate the arson or charge any suspects with the crime. One patron initially was a suspect, but denied any involvement in the attack. He was administered a lie detector test and passed. Another suspect is said to have admitted to the attack to a friend while inebriated, but police never actively pursued the lead and a year later that individual committed suicide at his girlfriend’s residence.

Horrible anti-LGBTQ jokes filled the radio airwaves in the aftermath. The Catholic Archdiocese and other churches in the city refused to allow funerals for the victims and many victims’ bodies were never claimed by their families. Four bodies were buried in a mass grave.

“Totally and utterly invisible our community was at that time—fear of being arrested, the fear of being put in an insane asylum, fear of losing your job, fear of isolating your family. I’m sure people lost friends that died in the fire, but the next day when they went to work they could not show their grief or talk about it,” said writer Frank Perez of the environment that loomed over the LGBTQ community at the time.

Within weeks, however, the community responded to the feelings of isolation in the wake of the attack. The Gay People’s Coalition formed offering counseling, health and STD services and a hotline number. The next year the community called the largest LGBTQ rights demonstration in the city’s history up until that time against bigot Anita Bryant who had just successfully overturned the Miami-Dade County’s Gay Rights Ordinance that offered protections against discrimination in housing and jobs.

Memorials to the victims of the UpStairs Lounge

This tragedy of the early LGBTQ movement would have been nearly forgotten if not for those who made special efforts to remember the victims through plays, books, documentaries and major art installations. A plaque lays on the sidewalk in memory of the victims. The play UpStairs is a memorial to the victims of the attack, written by playwright Wayne Self.

The play speculates on the challenges and aspirations of the unnamed victims of the attack, beginning with a song “Sanctuary” about the role of bars in the community that provided a safe place from day-to-day violence—as well as being a place of worship for MCC. Another song with the lyrics “I wish I could breathe” (lyrics that today evoke the rallying cry of the Black Lives Matter movement) shares the dream of living stable lives, expressing the at-the-time almost unfathomable idea of same sex marriage.

This is seen in the play in the relationship of two characters in love with each other, a Black gay street hustler and a white man who recently left his wife for him. The turmoil of their feelings most likely aptly expresses feelings and experiences of many in the LGBTQ community at the time who lived devoid of any support or endorsement of their relationships.

The play may not be far from the truth. Johnny Townsend, a 9th Ward resident who wrote an unpublished book about the bar said that the UpStairs Lounge “was a couple’s bar, the kind of place where a man would put together his companion’s birthday bicycle right there on the barroom floor, a place where customers would bring their own records to play on the juke box.”

The real memorial is to remember the victims of the UpStairs Lounge who gathered on that fourth anniversary of Stonewall to envision a future community that today celebrates the same sex marriage victory. This victory is for them. After all, they gave their lives for it.