|

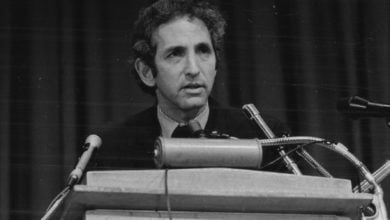

Forman was a principal organizer in the Civil Rights movement, a movement that shaped the progressive struggles that followed—the movement against the U.S. war on Vietnam, the women’s liberation movement and the struggle for LGBT rights. The Civil Rights movement fundamentally changed the United States.

The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee was the cutting edge of that movement. Forman was SNCCs main organizer and theorist.

Forman had a major impact on me when I got involved in the Civil Rights movement in Albany, Georgia, in 1962. A young African American man and I went to jail for trying to integrate a drugstore lunch counter. It was my first political act.

Shaped by outrage at racism and police brutality

Born in Chicago in 1928, Forman lived the first six years of his life on his grandmother’s farm in rural Mississippi. His grandmother raised nine children in a house without electricity or indoor plumbing. She survived and fed her family by subsistence farming, using only a plow and a mule. Forman then returned to Chicago, growing up on the South Side until he entered the Air Force. He served in Okinawa during the Korean War.

Forman attended the University of Southern California, but his time there was cut short when he was arrested on the steps of the school library. He had been studying at the library for the previous five hours. The Los Angeles police accused him of committing a robbery that had just taken place.

The police refused to enter the library where witnesses would have attested to Forman’s innocence. Instead, they took him to jail and severely beat him when he asked for permission to make a phone call. He was interrogated for two days before being released without apology. The savage brutality of the cops caused him to have a nervous breakdown and he needed hospital care before returning to Chicago.

Forman described the next six years as a time of ideas when he decided what to do with his life.

In Chicago, he enrolled in Roosevelt University, where he joined a group of students, faculty and community activists who united to struggle against racism. Influenced by the struggles in Ghana, Kenya and Montgomery, Alabama, Forman decided that a mass organization needed to be built.

Forman covered the struggle to desegregate Central High School in Little Rock for the Chicago Defender, a Black daily newspaper. He also became involved in supporting the struggle of sharecroppers in Fayette County, Tennessee, who were being evicted because they had registered to vote.

Forman built support both in Chicago, where he was teaching in a high school, and in Fayette, where he had gone to help. His experiences in both Little Rock and Fayette reinforced his ideas about what kind of organization was needed to fight racism in the United States.

He wanted to arouse the Black community and embarrass the government by playing upon the contradictions inherent in this society. This organization would use the tactic of nonviolent confrontation to agitate and organize demonstrations.

SNCC: Years of victories and struggle

All of Forman’s life experiences and studies prepared him for the position he took in 1961 as executive secretary of SNCC. He not only provided administrative leadership but also recruited and supervised a growing staff that stretched across the South. SNCC organizers agitated and built demonstrations that exposed the hypocrisy of “U.S. democracy” for the entire world to see.

Forman also participated in those activities, suffering numerous beatings and jailings. Under his leadership, SNCC became a major force in the Civil Rights movement.

As Claybourne Carson stated in his book, “In Struggle: SNCC and the Black Awakening of the 1960s,” “Immersed in sustained grass-roots efforts to overcome racial oppression, SNCC workers exemplified the distinctive values of those struggles. … The group was at the center of a movement that changed the nation and even more profoundly changed its participants.

“Forman provided a necessary ingredient in the development of an organizational structure for the southern student movement. Without a leader like Forman … it is unlikely that SNCC would have become a durable organization.”

Current NAACP chair Julian Bond agreed with this evaluation. “Without Forman, there would have been no SNCC. … Without SNCC it is doubtful that the movement would have succeeded as well as it did.”

Forman’s legacy extends to his writing, in particular his book, “The Making of Black Revolutionaries.” Not only does it give a history of the Civil Rights movement—its victories and defeats, its various participants—but it also indicts the capitalist system in the U.S. and its imperialist policies abroad.

Forman was an internationalist. He saw the need for collectivism and democratic centralism in any revolutionary organization. Forman knew such organizations must be rooted in the working class and the poor.

He saw nonviolence as a tactic. He validated the right of the oppressed masses to defend themselves against the violence of their oppressors in their struggle for liberation. As the Civil Rights movement evolved, he affirmed the need for Black leadership in the struggle.

Forman also connected the national struggle to the class struggle, proclaiming that basing one’s views on race alone is incorrect. He recommended that people read the writings of Marx, Lenin, Mao, Castro, Guevara, Ho Chi Minh, Fanon, Nkrumah and others to learn revolutionary theory on this most important question.

James Forman struggled to extend the Civil Rights movement—what amounted to a political revolution in the United States—to the social revolution in order to build a truly liberated society. He prepared the way. We must learn from his example and finish the task.