Ricardo Granda of the FARC-EP’s International Commission. Photo: Luis Acosta |

According to investigations carried out by the Venezuelan government, the kidnappers included corrupt elements of Venezuelan police and armed forces. They were paid $1.5 million by the Colombian government to carry out the abduction in Venezuela.

Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez denounced the kidnapping as a violation of Venezuela’s national sovereignty. In response to the Colombian government action, Venezuela recalled its ambassador from Bogotá and suspended all joint-development projects and trade relations with Colombia. Chávez demanded an apology from the Colombian government for the blatant violation of Venezuela’s borders.

To date, Colombian President Alvaro Uribe has refused to apologize. In fact, Uribe asserts that any future acts of aggression against other Latin American countries are justified if the Colombian government believes that they harbor “terrorists.” In January 2004, Colombian intelligence forces aided by the CIA helped capture FARC-EP leader Simon Trinidad in neighboring Ecuador. Trinidad was extradited to the U.S. in December 2004.

It would seem absurd that the Colombian government, with its notoriously brutal military-paramilitary terror apparatus and with a Congress where a third of the representatives boast of ties to the rightist death squads that brutalize the country, would be able to moralize about terrorism. Hundreds of trade unionists, peasant leaders and community leaders are assassinated every year by state-sponsored terrorism.

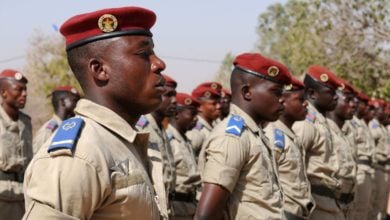

The U.S. has sent over $3 billion in military aid to Colombia over the past five years, including these military helicopters used to fight the country’s revolutionary movements. Photo: Eliana Aponte |

But the military policy of pre-emptive strikes against those deemed to oppose the interests of the Colombian government is almost identical to the policy of the Bush administration over the last few years. This is no coincidence.

The Colombian government is the largest recipient of U.S. military aid in the Western hemisphere. The U.S. has sent on the order of $3.5 billion in military aid to Colombia since 2000, and has sent hundreds of military advisors to train the Colombian military. The Colombian military is a virtual adjunct of the Pentagon.

Colombia’s role in Latin America is increasingly similar to the role that Israel plays for U.S. interests in the Middle East. Like Israel, Colombia is completely dependent on U.S. military and economic aid. Colombia is more and more acting as a U.S. garrison state in Latin America, exactly the role Israel plays to protect U.S. interests in the Middle East. The description of Israel’s relationship to U.S. imperialism in a Sept. 30, 1951 article in the Hebrew-language Ha’aretz—“Israel could be relied upon to punish one or several neighboring states whose discourtesy towards the West went beyond the bounds of the permissible”—could be applied nearly word for word today to Colombia in Latin America.

U.S. military aid to Colombia has traditionally been aimed at propping up the Colombian ruling class against popular rebellion and insurgency. Today, the aid has a foreign policy component. The Colombian government is increasingly striking out against leftist and nationalist movements in the region on behalf of the U.S. imperialist interests.

Venezuelan President Chávez pointed to this new fact as he explained the Colombian government kidnapping to a Jan. 24 rally of thousands of Venezuelans marching in support of Venezuelan national sovereignty after the kidnapping. “I know where this provocation comes from: from Washington, not from Bogotá!”(Xinhua, Jan. 25, 2005)

Washington was equally clear. When asked about the kidnapping of Rodrigo Granda and the subsequent tension between Colombia and Venezuela, U.S. Ambassador to Colombia William Woods replied, “We endorse Uribe’s action 100 percent.”

U.S. threatens Venezuela

The U.S. government has made a series of efforts to oust Chávez. It supported a coup attempt against Chávez in 2002. It has channeled millions of dollars to right-wing opposition groups connected to the Venezuelan ruling class, which have in turn gone toward fomenting economic sabotage against the government. On Jan. 18, incoming Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice told the Senate confirmation hearings: “We are very concerned about a democratically elected leader who governs in an illiberal way.” She has described Chávez’s government as being “a negative force in the region.” Washington has criticized Chávez’s “close relationship” with Fidel Castro.

The root of Washington’s hostility is the fact that Hugo Chávez represents the interests of the poor people of Venezuela—80 percent of the population. Since his election in 1998, Chávez has instituted many social and economic reforms that benefit poor and working people. The gains of the poor have come at the expense of the traditional ruling class, mainly large landowners and those who previously controlled the lucrative Venezuelan oil industry. Land has been expropriated on behalf of impoverished farmers. National oil funds are used to finance social programs like free health care and education for the poorest neighborhoods of Venezuela. The policies of the Chávez government are known collectively as the Bolivarian Revolution.

Chávez is perceived as a threat to U.S. hegemony in Latin America because he represents what can be achieved by a formerly colonized nation that decides to break away from U.S.-dominated economic institutions like the International Monetary Fund. Millions of Latin Americans are seeing Venezuela as an example of what a truly independent nation can accomplish—much in the same way that Cuba has been seen for the last 50 years.

Having been unable to engineer Chávez’s ouster by coup, and with hundreds of thousands of U.S. troops tied down in Iraq, the U.S. is desperately searching for a proxy power in Latin America to carry out its designs. Colombia’s Uribe government has been eager to cooperate.

Uribe supported the failed 2002 coup attempt against Chávez, even going so far as to offer political asylum and material support to the U.S.-backed Venezuelan coup plotters. In 2004, over 130 Colombian paramilitary death squads were sent to Venezuela to provoke violence, spreading terror among the public in another attempt to destabilize the political situation there.

‘I am Colombian. My president is Chávez.’ Caracas, Jan. 23, 2005 Photo: Howard Yanes |

The weakness of Washington’s plan to use the Colombian military as a strike force in Latin America is due to the growing anti-imperialist sentiment sweeping the continent. Venezuela’s poor and working people are every day more organized and ready to defend their Bolivarian Revolution against U.S. imperialism. Cuba continues to be a beacon for socialism as an alternative to the neo-liberal capitalism that has devastated millions of lives from Argentina to Mexico.

Within Colombia itself, the twin pillars of popular mobilization and armed insurgency are the Achilles heel of the Uribe regime. In October 2004, hundreds of thousands of workers stood up to paramilitary violence and staged a general strike against the government’s IMF-sponsored economic policies and death squad tactics.

In January and February 2005, the FARC-EP staged a series of devastating assaults on government military bases. This showed that the one-year-old “Patriot Plan”—the U.S.-sponsored military offensive against the FARC-EP—has not weakened the communist organization or its mass base of support.

These different rebellions and uprisings are steadily merging into a common anti-imperialist struggle. At the December 2004 Second Bolivarian People’s Congress held in Caracas, Venezuela, more than 200 leaders of popular movements gathered to share experiences and discuss strategies for advancing the struggle.

“This Second Congress reaffirms the decision to struggle together for our definitive independence,” the final declaration noted, “in the historic moment of a favorable change in the correlation of forces in favor of the people in Latin American and the Caribbean.”