“Judge Roberts is the kind of outstanding nominee that will make America proud. He embodies the qualities America expects in a justice on its highest court: someone who is fair, intelligent, impartial and committed to faithfully interpreting the Constitution and the law.”

— Senate Majority Leader Bill Frist

Bush Supreme Court nominee John G. Roberts. Photo: G. Fabiano/SIPA Press |

The United States Supreme Court, the highest court in the country, is now the focal point of a widely discussed controversy. It involves George Bush’s recent nominee to fill the recent vacancy on the Court—John G. Roberts. Many progressive organizations are opposing Roberts because of his reactionary views.

Less than 24 hours after Bush announced Roberts’ nomination, groups like Planned Parenthood and NARAL Pro-choice America, called people to protest his nomination. Roberts is against women’s reproductive rights. He has openly said that Roe v. Wade—the 1973 Supreme Court decision legalizing abortion in the United States—“was wrongly decided and should be overruled.” (CNN.com, July 20)

Roberts’ credentials also reveal his racist positions on affirmative action and voting rights. When he was a lawyer in the Reagan administration, “Mr. Roberts express[ed] hostility to affirmative action programs and to a broad application of the Voting Rights Act. Mr. Roberts was vocal about making certain that [the Voting Rights Act] apply only to practices that were intended to harm minority voters—not to those that simply had the effect of doing so.” (Washington Post, July 31)

This controversy swirling around Roberts’ nomination is not new. Under the U.S. Constitution, justices are appointed to the Court for life by the president and confirmed by the Senate. Over the past decades, right-wing nominees have provoked mass outrage and protest, largely based on the fear that a conservative Supreme Court could single-handedly roll back hard won progressive social gains. In 1987, Robert Bork, a Reagan appointee, had his nomination rejected in the Senate after mass protests by women’s and civil rights groups.

But a debate focusing on the political positions of Roberts or any other individual nominee is ultimately too narrow. While racist, anti-woman judges should be opposed, revolutionaries should understand the nature of the Supreme Court itself and its role in maintaining bourgeois rule. Supreme Court justices, politicians and the rest of the ruling elite do not make decisions independent of the political climate in society and the balance of forces in the general class struggle.

A consistently reactionary institution

Throughout its history, the Supreme Court has been one of the most consistently reactionary institutions of the U.S. government. The court has never been an “objective” or “impartial” check on the legislative and executive branches of the government. Rather, it was shaped to serve as the main arbiter for protecting capitalist interests. These interests shifted over time and the Supreme Court shifted with them. The Supreme Court uses the cover of “impartiality” to hide its true function. The court is an integral part of the capitalist state.

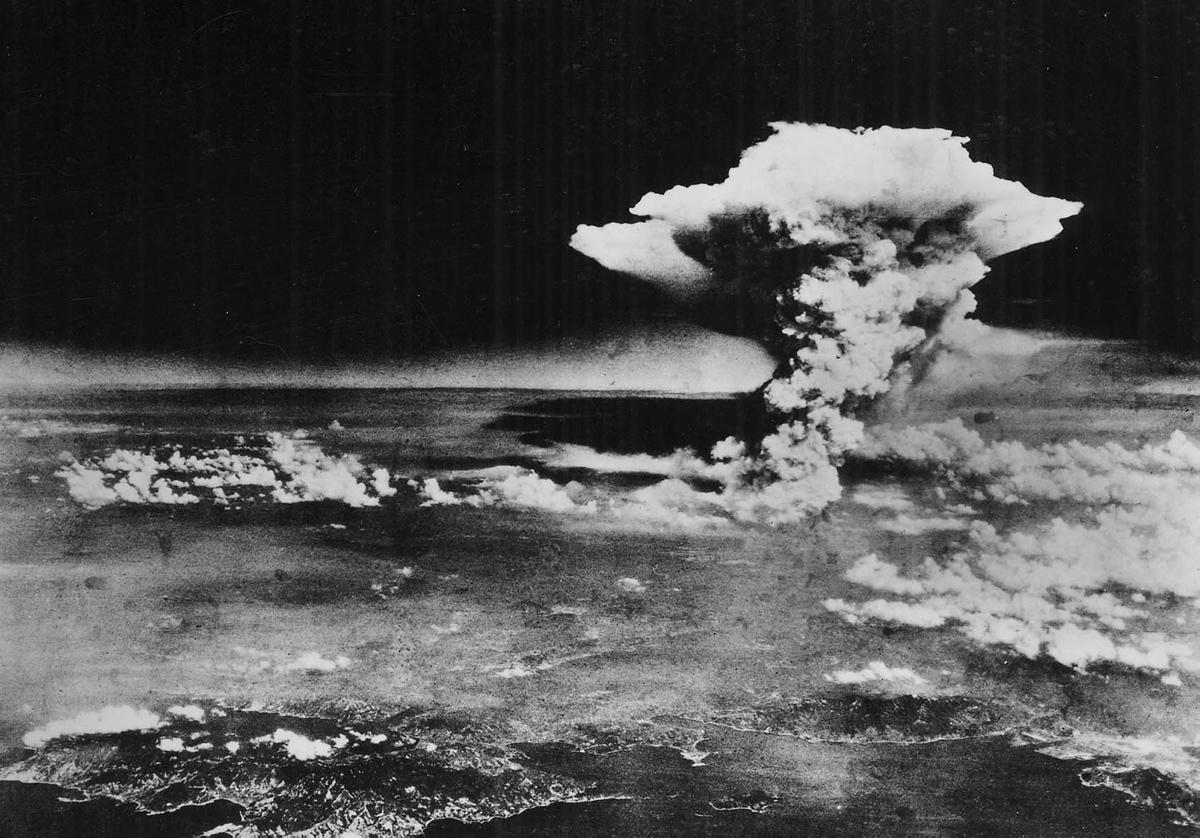

Korematsu v. U.S. legalized the internment of Japanese-Americans during World War II. Photo: Hulton Getty Photo Archive |

Article III of the U.S. Constitution created the Supreme Court to interpret the “constitutionality” of the laws passed by Congress. Its role soon expanded as greater power was needed. The case of Marbury v. Madison in 1803 was the first instance in which a law passed by the elected representatives of Congress (that, is representatives of those who had the right to vote in 1803: white males who owned property) was declared unconstitutional. This decision greatly expanded the power of the Court by establishing its right to overturn acts of Congress, a power not explicitly granted by the Constitution.

Subsequently, the court has consistently issued decisions enforcing the prevailing political sentiments of the dominant sector of

the U.S. ruling class. In the 1857 Dred Scott v. Sandford case, the court found that Scott, a slave who sued for his freedom, could not sue in federal court because Black people were not citizens. The slavocracy—which dominated the U.S. government, as opposed to Northern industrial capital—held onto slavery as long as they could.

The Plessy v. Ferguson case in 1896 held that “equal but separate accommodations” for Blacks on railroad cars were legal. This ruling enforced and promoted “Jim Crow,” the euphemism for the apartheid police-state in the southern part of the United States.

Later, when all elements of the capitalist class were oriented toward war in World War II, the Supreme Court gave its stamp of approval to the internment of over 100,000 Japanese Americans in Korematsu v. United States. President Franklin Roosevelt initiated the interment by executive order. It was in the bourgeoisie’s interests to demonize and scapegoat Japanese immigrants during the war, so the court dutifully found Roosevelt’s racist action “constitutional.” Here too, the court upheld vicious institutionalized racism. There were no internment camps for German-Americans during World War II.

The Supreme Court has also been nearly 100 percent consistent in its decisions involving the labor movement. Before the 1930s, injunctions and violent strikebreaking were always considered legal. After the passage of the Wagner Act in 1935, the court didn’t change its course. It has continued to side with the bosses, working to erode already weak labor laws.

Rulings came from below

Despite the deeply right-wing nature of the Supreme Court, it has been forced to respond to the mass movement in numerous rulings, especially during the last 50 years.

After years of forging unprecedented multinational unity and strength in the general mass upheaval of the 1930s, especially in the sharecroppers unions, things weren’t improving for African Americans in the South. Segregation was still permitted and racist lynchings happened frequently. The great majority of Black people lived in grinding poverty.

The specter of a potential rebellion due to social conditions, coupled with the beginnings of civil rights organizing in the early 1950s, pushed the Supreme Court to rule that “separate is not equal” and order desegregation of schools in Topeka, Kansas. The case was Brown v. Board of Education, decided in 1954.

Brown v. Board of Education was a step forward at the time. It gave the growing Civil Rights movement a legal decision to use for further mobilization. Legislation passed a decade later—the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965—further extended the legal rights of African Americans.

But these laws were only passed after the massive struggle of Black people began to challenge the entire ruling class in the United States. The Civil Rights movement was more than a few pickets and demonstrations. Millions of people were in motion.

It was only when the capitalist class became afraid of massive social change that it passed the laws and enforced them in their courts. To the capitalists, the end of legalized segregation of African Americans became more palatable than insurrection. Neither the Supreme Court nor Congress would have given an inch without massive pressure from below.

The Court’s ruling in Roe v. Wade legalizing abortion was also the result of widespread struggle. Only after years of mobilizing and fighting for reproductive rights did the government officially recognize abortion rights. The women’s movement demanded equality and self-determination over their own bodies.

The women’s movement grew in scope and militancy in the prevailing climate of radical struggle at the time. The Civil Rights movement had won great gains and spawned a militant movement for Black liberation. Other national liberation movements like the Puerto Rican and the Native movements were also gaining popular momentum. Anti-war forces propelled millions into the streets. And the modern gay rights movement was pushing for change.

With society in upheaval, the court had no choice but to recognize women’s reproductive rights. It didn’t matter that the court was led by a conservative Nixon appointee—Chief Justice Warren Burger (he voted to reinstate the federal death penalty three years later); the ruling class had to give in. They feared increasing instability and challenge from the women’s movement and the national liberation movements.

Struggles ahead

For activists and workers, it is important to know that the Supreme Court is not where real change occurs. Whatever its actions in a given case, it ultimately serves the interests of the capitalist class, giving its repressive, anti-people laws the stamp of respectability.

The appointment of a right-wing racist like John Roberts can be the basis for bringing new layers of young people into struggle against the U.S. government. That will be a welcome development.

Some forces will try to channel that struggle into support for the Democratic Party. Of course, even though the Democrats are a minority in the Senate, they could stop Roberts’ nomination through filibusters or other tactics. But history shows that they will never lead the struggle against racist or sexist reaction.

The best way to challenge the Roberts nomination and to protect women’s rights and civil rights is to strengthen and broaden the growing mass movement against imperialist war, racism and cutbacks. An effective, mass-based struggle can turn around any appointment.

That way, no matter who is appointed, the capitalist class—along with the Supreme Court whose interests it serves—will have to think twice about trying to roll back women’s rights, affirmative action, voting rights, or any other gain.

It was a mass movement that won those rights. A mass movement can defend them—and extend them.