Among the many outstanding revolutionary figures of the 20th century, one of the most remarkable was the Vietnamese leader Ho Chi Minh. In order to achieve the liberation of his country, the national liberation movement he led for nearly 40 years had to defeat not one, but two, of the world’s major imperialist powers—France and the United States—and withstand five years of Japanese occupation.

Without a revolutionary party and leadership, Vietnam’s victory would have been unthinkable.

Ho Chi Minh was the founding leader of the Indochinese Communist Party (later the Vietnam Workers Party). Ho was also a founding member of the French Communist Party a decade earlier. The position of Lenin and the Bolshevik Party on supporting the right of oppressed nations to self-determination was key in winning him over to communism.

In addition to his great achievements, Ho Chi Minh—popularly known as Uncle Ho—was revered for his simple lifestyle and revolutionary dedication. As countless witnesses testified over the years, this was no pretense. Elected president, he refused to live in the palace inherited from the colonial era, preferring a modest house with a garden.

Early life

Ho was born on May 19, 1890, in a tiny village in Nghe An province of central Vietnam. Nghe An was an area renowned for resisting foreign domination and French colonialism. His father was a Confucian scholar and civil servant who lost his position in the early 1900s because he opposed French colonialism and its Vietnamese elite collaborators.

French colonization of Vietnam and the rest of Indochina, including Laos and Cambodia, had begun in the 1830s. By the 1880s, the takeover was complete.

French exploitation of Vietnam was ruthless and brutal. Contrary to the colonizers’ claim of “bringing civilization” to a country whose existence and culture was more than 1,000 years older than their own, only a very thin layer of the Vietnamese elite shared in the vast wealth extracted from the land and people.

An indicator of the deteriorating conditions under French rule was a sharp decline in literacy in Vietnam in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Hundreds of thousands of peasants died or were permanently disabled by corvée (slave) labor to build roads, ports and other projects that opened the country up to French capitalist profiteering. The colonizers levied crushing taxes on the rice-growing small farmers who constituted the vast majority of the population.

From student to world traveler

In 1908, this combination of heavy taxes, forced labor and rising anti-colonial sentiment led to a series of demonstrations and rebellions. On May 9, large numbers of peasants converged on the imperial capital of Hue.

At that time, Ho was known by the name his father had given him at 10 years old, Nguyen Tat Thanh. He had been studying at the National Academy in Hue. Ho joined the demonstration, offering to serve as an interpreter for the protestors since he was studying French.

The demonstration ended with French troops opening fire and killing many. Ho was beaten and the next day, nine days short of his 18th birthday, was expelled from the academy. From that point on, he was on the French secret police surveillance list, along with his father and brother.

In 1911, Ho left Vietnam, signing on as an assistant cook on a French ocean liner, the first of many jobs aboard ships. His workdays typically lasted 17 hours and included washing pots and pans, cleaning floors and shoveling coal.

His travels and experiences during those years would profoundly shape his views as a communist and internationalist.

Over the next decade, Thanh worked ocean-going ships, in the kitchens of fancy restaurants in New York, Boston, London and other cities, as a boiler operator and as a photo retoucher. As a seaman, he traveled to other French colonies, including Senegal, Madagascar, Algeria, Tunisia and Morocco.

“The French in France are all good. But the French colonialists are very cruel and inhumane,” he commented. “To the colonialists, the life of an Asian or an African is not worth a penny.”

In 1912 to 1913, Ho lived in the United States. He attended Harlem meetings of the United Negro Improvement Association, the organization led by Marcus Garvey. He also traveled to the South, where he observed a Ku Klux Klan lynching. Ho arrived believing that the United States was not an imperialist country and might help Vietnam win its freedom. He left disabused of any such notion.

His incisive writings about lynching and the KKK’s racist and anti-working class role were published in French and Soviet newspapers in the 1920s.

Organizer and communist in France

From the United States, Ho relocated to Britain and then to Paris, becoming active in trade union and socialist politics. In 1919, he organized an association of Vietnamese living in France. The same year, he authored a petition to the post-World War I Versailles conference.

The petition called on President Woodrow Wilson and the other victorious allied powers to extend Wilson’s renowned “14 Points” and advocacy of the right of self-determination to the colonized peoples of Southeast Asia. Representatives of other oppressed peoples in Asia and Africa sought similar redress. All were turned away.

The allied leaders’ speeches about “democracy” and “self-determination” were proved to be nothing more than propaganda. Once the war was over, the victorious empires, particularly the British and French, expropriated the colonies of their defeated German, Austrian and Turkish rivals.

Ho’s petition catapulted him to fame, making him the best-known Vietnamese in France and the subject of intense police surveillance. He changed his name and for the next two decades was known as Nguyen Ai Quoc.

At the age of 30, Ho emerged as a tireless organizer, writer and advocate of national liberation and socialism. In the aftermath of the Russian Revolution of 1917, the world socialist movement was splitting into revolutionary and reformist wings. Ho was involved in the struggle raging inside the French Socialist Party. The decisive element for him was reading Lenin’s “Theses on the National and Colonial Questions.”

“There were political terms difficult to understand in this thesis,” he wrote. “But by dint of reading it again and again, finally I could grasp the main part of it. What emotion, enthusiasm, clear-sightedness and confidence it instilled in me? I was overjoyed to tears. Though sitting alone in my room, I shouted aloud as if addressing large crowds: ‘Dear martyrs, compatriots. This is what we need, this is the path to our liberation.’”

Unlike Wilson’s hypocrisy, Lenin not only advocated the destruction of colonial empires but also insisted that support for the struggles of the colonized peoples must be a priority of the revolutionary workers parties inside the imperialist countries.

Ho was a delegate to the founding convention of the French Communist Party in 1921 and an organizer of the Inter-colonial Union, made up of revolutionaries from France’s African, Asian and West Indian colonies. He edited and distributed its publication, “The Pariah,” a unique source of anti-colonial agitation that was outlawed by French colonial authorities and had to be smuggled.

Returning to Southeast Asia

In danger of arrest by French secret police who watched him around the clock, and desiring to begin organizing in his homeland, Ho slipped out of France in 1923. He left for the center of world revolution, the newly formed Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. In the Soviet Union, he worked as part of the Communist International.

After nearly two years in Moscow, Ho was sent, at his request in 1924, to Guanzhou in southern China, then in the midst of revolutionary upheaval, under the cover of being a reporter for a Soviet newspaper. His real mission was to begin building a revolutionary party along Leninist lines in Indochina. The subterfuge was necessary because the French secret police were on the lookout for Ho.

He started by organizing the Revolutionary Youth League, made up mainly of young Vietnamese nationalists who had fled to southern China to escape French repression. Revolutionary unrest was spreading in Vietnam. The youth league was organized along Leninist organizational lines, and served as the predecessor to the Indochinese Communist Party, founded in 1930.

After participating in a series of uprisings against French rule, the ICP was severely repressed in 1931 and many of its future leaders were imprisoned. The French got their fellow imperialists, the British, to arrest Ho in Hong Kong in 1931, where he narrowly escaped execution. In 1933, he escaped, was reported killed and was memorialized by the Communist International and mourned in Vietnam. He resurfaced in China five years later, in 1938.

In 1940, France was defeated and occupied by Nazi Germany. The new Nazi-controlled Vichy government in France took over in Vietnam. The Vichy French were allowed to continue administering Vietnam by the new rulers, the Japanese Empire. Vietnam was now under double colonial rule.

The war of independence

The following year, after three decades of exile, Nguyen Ai Quoc returned to Vietnam together with other leaders of the ICP. They launched the League for the Independence of Vietnam, also known as Viet Minh, in 1941, beginning a guerrilla struggle against the French and Japanese occupiers that would last four years.

Nguyen Ai Quoc adopted a new name: Ho Chi Minh.

In early 1945, after the collapse of the Vichy regime, Japan took over direct control. The Japanese occupiers continued to export rice from Vietnam even as severe famine hit the country. Between 1.5 and 2 million of the 10 million Vietnamese died in the famine. The Viet Minh distributed confiscated food supplies to the hungry. The organization grew exponentially in size, as did the party. In August 1945, Japan surrendered to the United States, ending World War II.

On Sept. 2, 1945, Ho Chi Minh declared Vietnam’s independence to an assembly of more than 500,000 people. He indicted the French colonizers: “In the field of politics, they have deprived our people of every democratic liberty. … They have enforced inhuman laws; they have set up three distinct political regimes in the North, the Center and the South … in order to wreck our national unity and prevent our people from being united. They have built more prisons than schools. They [have] mercilessly slain our patriots; they drowned our uprisings in rivers of blood. … They have robbed us of our rice fields, our mines, our forests and our raw materials.”

Hoping to gain the support—or at least the neutrality—of the United States, whose pilots the Viet Minh had helped during World War II, Ho’s speech borrowed language from the U.S. Declaration of Independence. Washington was unmoved. On the contrary, U.S. troop carrier ships ferried the French army back to Vietnam. Starting with Truman, the next six U.S. presidents would all wage war against the Indochinese peoples. Despite all efforts by Ho and other Vietnamese leaders to negotiate a settlement, the French re-occupation left the Vietnamese with two choices: surrender or fight. They chose to fight.

The French believed that the war would be short and that victory was inevitable. In their colonial arrogance, they severely underestimated the resolve, resourcefulness and strategic thinking of the Vietnamese leaders. Every year, the French commanders issued proclamations that victory was near, that Vietnamese forces were weakening and could not hold out much longer. By 1954, the United States was paying more than 75 percent of France’s Indochina war budget.

But the same year, the Vietnamese scored a decisive military victory, killing 7,000 French troops and capturing 11,000 more. The battle of Dien Bien Phu signaled an end to French colonialism in Indochina, but not the end of imperialist intervention.

The fight for unification

The 1954 agreement in Geneva, “On the problem of restoring peace in Indochina,” called for the “temporary” division of Vietnam at the 17th parallel into two zones.

In the north, the Democratic Republic of Vietnam was established. It was led by the victorious liberation forces, the communist party, renamed the Workers Party, and Ho Chi Minh. They immediately began the process of land reform and socialist construction.

In the south, a government was set up headed by former Japanese and French puppet emperor Bao Dai and his U.S.-appointed prime minister, Ngo Dinh Diem. According to the Geneva accords, a countrywide election was to be held within two years. But Washington did everything possible to make the “temporary” division of Vietnam permanent and to block the election.

The reason was no mystery. President Dwight Eisenhower later said: “I have never talked or corresponded with a person knowledgeable in Indochinese affairs who did not agree that had elections been held as of the time of the fighting, a possible 80 per cent of the population would have voted for the communist Ho Chi Minh as their leader.”

Despite these attempts to keep the nation divided, large swaths of southern Vietnam were in the hands of Viet Minh forces, which had set up popular and efficient governments in those areas. The brutal, corrupt and virulently anti-communist Diem regime soon launched a campaign to physically destroy the liberation forces and restore landlord rule in the countryside.

In 1960, the National Liberation Front was established in southern Vietnam. Its aim was to defeat the neocolonial Diem regime and reunite the country. Within three years, it was on the brink of victory. Only the intervention of hundreds of thousands of U.S. troops and the most intense bombing campaign in history delayed the Vietnamese victory. The U.S. war killed millions of Vietnamese and inflicted massive destruction on the country. On the U.S. side, 58,000 were killed and 300,000 wounded.

But despite the Pentagon’s reign of death, the Vietnamese were not to be defeated. On April 30, 1975, the armed forces of the north and of the National Liberation Front entered Saigon, the southern capital, ending the war. Shortly thereafter, Saigon was renamed Ho Chi Minh City.

Ho Chi Minh did not live to see that day; he had died on Sept. 2, 1969. What lived on and ensured that world historic defeat of U.S. imperialism was the party that Ho had dedicated his life to building.

Ho’s testament, written a few months before his death, expressed his full confidence that victory was certain. “We, a small nation, will have earned the unique honor of defeating, through a heroic struggle, two big imperialisms—France and the United States—and making a worthy contribution to the national liberation movement.”

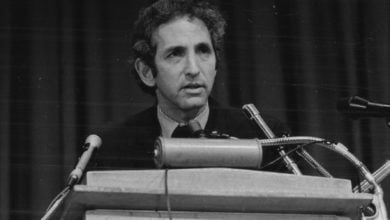

Ho Chi Minh addresses a meeting of French communists in Tours in 1920.

Anti-colonial liberation leader, 1954

The North Vietnamese Liberation Army, led by Ho and the Vietnamese Workers Party, succeeded in defeating U.S. imperialism.