The writer is a member of the Echo Park Community Coalition and the Alliance for Just and Lasting Peace in the Philippines in Los Angeles.

When the Comprehensive Immigration Reform Bill died in the U.S. Senate last June, many Filipinos in the United States were disillusioned.

Skeptics just shrugged their shoulders and accepted that they live in a racist nation that hates immigrants, especially

|

Out of the more than 3.5 million Filipinos in the United States, around 3,000 actively participated in the immigrant rights upsurge from March to May 2006. And yet, Filipinos are suffering repression like all other immigrants. More than 4,000 Filipinos have been deported since 2001.

It is important to understand the history and the present situation of Filipino immigrants in the United States.

The first known large-scale immigration of Filipinos started after the Philippines were occupied by the United States on August 13, 1898.

The first Filipino migrant workers, 15 Ilocano peasants, were employed as sugar cane planters and cutters. They arrived in Hawaii in 1906. (At the time, Hawaii was a U.S. colony.—Ed.) This is the first recorded historical note of Filipino migration to the United States. Thus, the Filipino American community celebrated the first century of Filipino workers’ migration to the United States last year.

This differs from some historians’ romantic notions that Filipino immigration started when Filipino seamen in the galleons jumped ship and started Filipino settlements in the United States.

It is a controversial subject that should be studied and discussed and proven by facts.

The Filipino population grew from 15 to 39,470 from 1910 to 1930 in Los Angeles. From 1920 to 1930, Filipinos established “Manila towns” in Seattle, Los Angeles, Chicago and San Francisco.

Before the start of World War II, Filipino farmworkers, cannery workers and pensionados lived in America.

Racism against immigrants

Historical records show that there were at least 15,000 Filipino scholars who studied in the United States as pensionados. Many of them went back to the Philippines to serve as teachers, bureaucrats and loyal “U.S. nationals” in government, private and civil service jobs.

In 1934, the Tydings-McDuffie Act—the U.S. law that made the Philippines a commonwealth and promised independence after 10 years—restricted Filipino migration to 50 persons allowed to enter the United States each year. The limit was not repealed until 1946.

These policies were a product of anti-Asian sentiments that had brewed in the United States against Chinese and Japanese communities for some time.

Earlier the U.S. had passed the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, the anti-miscegenation law of 1905—that prohibited inter-racial marriage—and the National Origins Act of 1924, which prohibited Japanese migration.

Filipinos in the United States were subjected to lynching and anti-foreign riots until the 1950s and blatant racist actions.

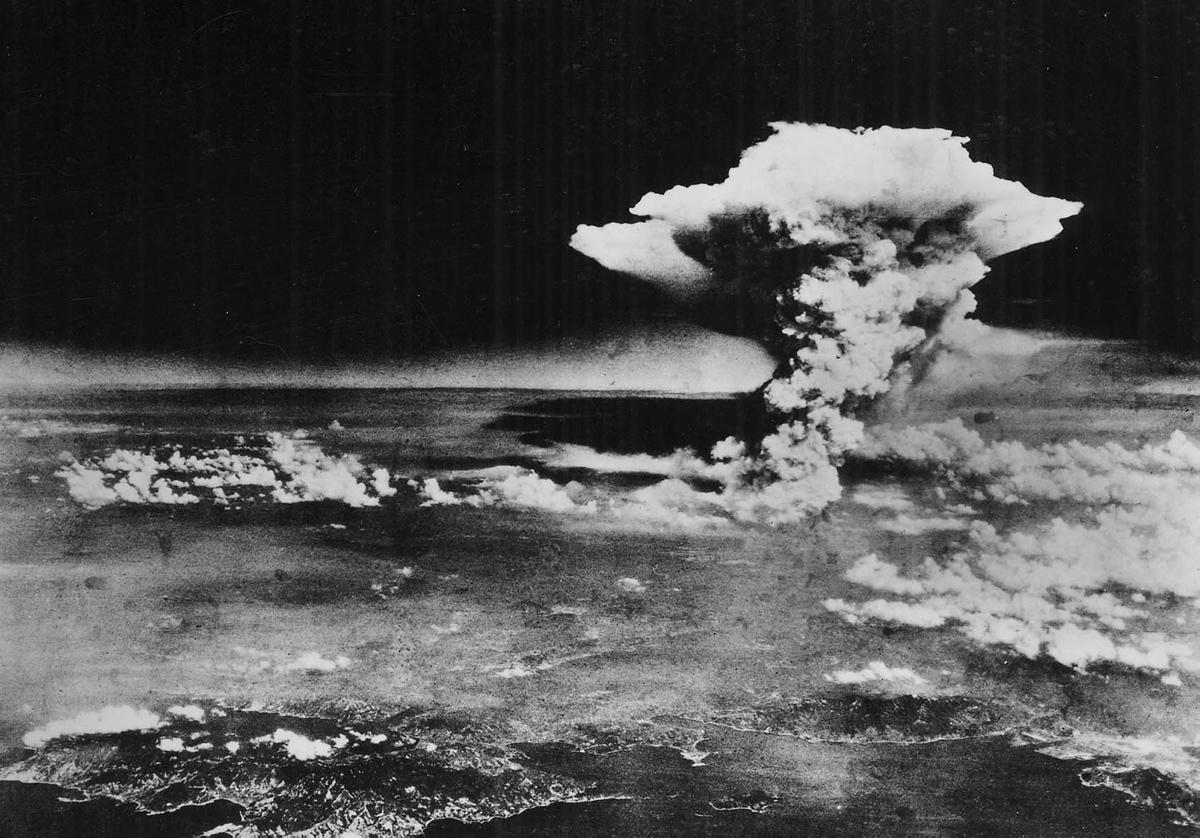

World War II changed the situation.

During and after the war, Filipinos gained citizenship by joining the U.S. Army and the Navy. San Diego, Long Beach, Virginia Beach, Alaska and other places blossomed with large Filipino populations due to this military employment.

By World War II, there were at least 300,000 Filipinos in the United States.

Immigration reform law of 1965

In the 1960s, a new immigration reform law was passed. Concomitant to the law was the family reunification law that allowed families from Asia to come to the United States.

This started the “brain drain” phenomenon that happened in the Philippines and the rest of Asia. Tens of thousands of professionals—doctors, nurse, teachers, engineers—migrated to the United States, Canada and other parts of the world.

The declaration of martial law in the Philippines in 1972 and the installation of a fascist dictatorship hastened more migration to the United States.

More than 5,000 Filipinos, mostly political refugees, sought protection from the Marcos dictatorship by immigration to the United States, but less than 1 percent got political refugee status.

By the 1990s, Filipinos became one of the largest Asian migrant populations in the United States—more than one

|

By the 1980s the traditional farmworker population of Filipinos had died out. It was replaced by a larger population of Filipinos whose families sent their children to school, by newly arrived professionals, and by Filipinos serving in the U.S. military and their dependents.

The 2000 U.S. Census counted 2.8 million Filipinos in the United States. More recent estimates put the number at 3.5 million by 2006. At least half of them are women. An estimated 850,000 undocumented Filipinos live in the country.

Many U.S. cities have sizable Filipino populations, including San Diego, San Francisco and Los Angeles. More than 1.5 million Filipinos are based in California.

Other areas with concentrations of Filipinos are New York City; Las Vegas, Seattle, Chicago, Washington, D.C. and the surrounding region.

World War II veterans’ issues

An important issue for the Filipino American community is the status of veterans of World War II.

On July 27, 1941, the 120,000-strong Philippine armed forces under the Commonwealth government were conscripted by the United States through a military order of President Roosevelt. They formed the bulk of the United States Armed Forces in the Far East (USAFFE).

When World War II broke out and after the USAFFE surrendered in May 1942 to the Japanese, Filipino guerilla forces ballooned to more than 200,000 under American and Filipino officers.

But on Feb. 18, 1946, after the war ended, the U.S. Congress passed the Rescission Act. The law did not recognize the military service of Filipinos during World War II. It denied them veterans’ benefits.

More than 30,000 Filipino WWII veterans had come to the United States by 1991. They acquired automatic citizenship due to the immigration reform act of 1990.

Only 11,000 are still in the United States today. They are discriminated against.

They are not recognized as American veterans and have lived in poverty. The poverty and neglect is similar to that of their fellow veterans, many of whom are homeless and destitute in the United States.

But in 1984, the Filipino veterans and the community started to organize, demanding recognition and full benefits. By 1993, mass actions started. The movement gained momentum.

After 61 years and 18 years of continued advocacy, hopes are brighter for the passage of an equity bill that will give pensions to the remaining 18,000 Filipino veterans both in the United States and in the Philippines.

The present situation

U.S. Census data tells us where Filipinos work in the United States: 37 percent are in precision production, crafts and repair; 27 percent are operators, fabricators and laborers; 24 percent are in technical, sales, administrative and service occupations; and 11 percent hold managerial positions.

Based on this information, it is safe to assume that vast majority of the Filipinos belong to the working class. They are victims of the economic doldrums that the United States has suffered in recent years.

This data belies the claim of some fake economists that Filipinos in the United States are rich, that remittances from Filipino workers overseas can support the Philippines’ economy and that this phenomenon is a deterrent to revolution in the Philippines.

Fifty percent of the $12 billion in remittances from all Filipino overseas workers comes from the United States and Canada.

The Filipino American community in the United States continues to flex its muscles. Filipinos might not have economic or political clout in this country, but they are slowly coming out of their shells and are being noticed.

The last years of Martial Law in the Philippines from 1983 to 1986 saw the political activities of the Filipinos surge in the United States.

The immigrant rights upsurge in 2006 showed that more Filipinos, especially American-born activists, are willing to come out and speak for their community. This is increasingly the case. It is a phenomenon worth watching and monitoring.

Together with the Latino community and other immigrants and their allies, Filipinos will continue to fight for real immigration reform and community empowerment.