Today’s world monetary system is based on the “dollar standard,” also known as dollar hegemony. This is the unstable system that in the early 1970s replaced the previous system for settling international transactions, agreed to by delegates of 44 allied countries meeting in Bretton Woods, N.H., in July 1944.

The Bretton Woods system was a partial return to the international gold standard that had prevailed for most of the 19th century, when Great Britain was the dominant industrial power. The gold standard could not be maintained for long after Britain lost its dominant position, challenged especially by the rise of the United States and Germany in the late 19th century and beyond. It was finally abandoned during the great world crisis of the 1930s.

Under the Bretton Woods system, sometimes referred to as the “dollar-gold exchange standard,” the dollar was tied to gold, the universal measure of commodity value, at a fixed rate of $35 per ounce, and other currencies were tied to the dollar, also at fixed exchange rates. In other words, although prices and debts were denominated in dollars, the dollar itself was defined as 1/35 of an ounce of gold, and so indirectly dollars and debts were still denominated in gold.

International trade imbalances were settled in dollars rather than gold, but countries ending up with excess dollars could at any time exchange them for gold at the U.S. Treasury. In contrast to the policy under the classic gold standard, U.S. citizens were not allowed to turn in paper dollars for gold.

U.S. hegemony begins to erode

The Bretton Woods system was initially quite stable, based on the reality that the United States had become the dominant capitalist power by the end of World War II. That stability began gradually to erode, however, as U.S. industry faced increasing competition, especially from Germany and Japan as those countries rebuilt after the war, and after the United States became bogged down in the un-winnable Vietnam War.

Partially as a result of the mounting costs of the war, and following the great Tet offensive of the Vietnamese liberation fighters in early 1968, the United States experienced a run on (flight from) the dollar and was forced to abandon the Bretton Woods system—at first temporarily (it was hoped), then permanently.

While U.S. economic hegemony had become seriously compromised by the 1970s, U.S. military supremacy remained in place. This, along with an end to the Vietnam War, made it possible to replace the Bretton Woods system by the dollar standard. That system, though increasingly shaky, continues to underlie international trade and finance to this day.

Under the new dollar standard, prices and debts were (and are) no longer defined in specified weights of gold but in terms of the ever-changing gold value of the dollar, as reflected in the prices set daily on the London Metal Exchange. Exchange rates between currencies are not fixed but fluctuate constantly—depending on trade balances, relative interest rates and economic conditions prevailing in the different countries, and central bank manipulation.

Most raw materials, most importantly oil, are priced in—and therefore bought and sold for—U.S. dollars. Hence, dollar-denominated U.S. Treasury debt—bonds, notes and bills—have until recently been the desired reserve holdings of most countries.

To better understand the dollar standard, consider this example: Imagine that you can’t meet a mortgage payment on your house of $2,500 a month. But then imagine that your mortgage contract includes a provision that allows you to make the payment in 2,500 half dollars, or 2,500 quarters, dimes, nickels, or pennies, or even 2,500 fractions of a penny. You’ve got to pay 2,500, but it can be 2,500 of anything you want. This way you will not go bankrupt or lose your home. That, in essence, is the dollar standard.

Despite being an inherently unstable monetary system, the dollar standard, backed by U.S. military might, has allowed the United States to run chronic and growing trade and budget deficits for many years. As a result, the United States has been transformed from the world’s biggest creditor in the early 1970s to the biggest debtor today—the debt, of course, denominated in dollars.

An unsustainable relative prosperity, based largely on massive borrowing, emerged in the 1980s that benefited the United States and its main trading partners, while U.S. industry continued its long-term decline.

The U.S. labor movement, led by an officialdom steeped in class-collaborationist “business unionism” as opposed to class-struggle policies, shrank in size and power, and corporate take-backs robbed workers of gains from previous struggles. A rising mountain of debt propped up living standards in the United States, but the infamous “race to the bottom” had begun.

The fall of the Soviet Union in 1991, by opening a vast area of the world to capitalist exploitation and removing a major check on U.S. imperialism, reinforced dollar hegemony. China’s “opening up” to large-scale foreign direct investment had a similar effect.

Too many dollars

But now China and other major exporters, including Russia and other oil-exporting countries, are accumulating dollar reserves far in excess of what they need or desire. Moreover, the dollar has declined steeply for the last six-plus years against both the euro and gold, causing massive losses for countries holding large amounts of dollar-denominated debt.

Big private investors are more and more shunning the dollar, and many countries have begun diversifying their reserves. Some countries, including China and some oil exporters have set up “sovereign wealth funds” that will buy up shares in U.S. corporations and other valuable assets.

Most recently, the Abu Dhabi Investment Authority, the world’s largest such fund, purchased a 4.9-percent stake in banking giant Citigroup for $7.5 billion. The investment by this Gulf Arab emirate is in the form of convertible securities paying 11-percent interest, well above the current average for U.S. junk bonds. For Citigroup, desperate for fresh capital owing to massive losses stemming from the subprime mortgage crisis, this was an offer it could not refuse.

Telling it like it is, or may be soon

Leaders of several oppressed countries have recently issued pertinent comments on the declining dollar and U.S. hegemony.

Fidel Castro, for example, in his “Reflection” of Nov. 15, 2007, referred to former Federal Reserve chief Alan Greenspan’s recently published memoir, “The Age of Turbulence,” stating that the book “clearly reveals how imperialism seeks to continue buying up the world’s natural and human resources with perfumed paper bills.”

In a previous Reflection, dated June 17, 2007, Fidel wrote: “Based on the privileges granted to the United States in Bretton Woods and Nixon’s swindle when he removed the gold standard which placed a limit on the issuing of paper money, the empire bought and paid with paper tens of trillions of dollars, more than twelve digit figures. This is how it preserved an unsustainable economy. … Today, the value of one dollar in gold is at least eighteen times less than what it was in the Nixon years. The same happens with the value of the reserves in that currency.

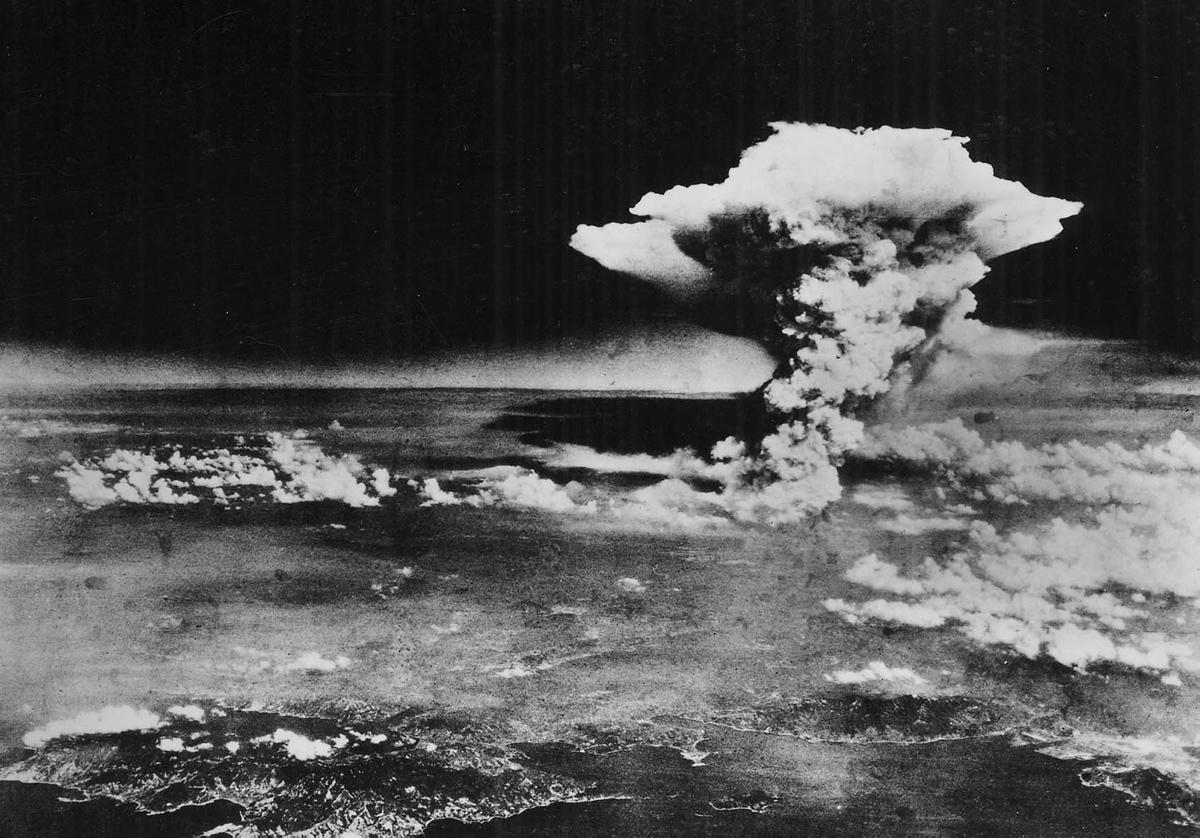

“Those paper bills have kept their low current value because fabulous amounts of increasingly expensive and modern weapons can be purchased with them; weapons that produce nothing. … With those same paper bills, the empire has developed a most sophisticated and deadly system of weapons of mass destruction with which it sustains its world tyranny.”

In Tehran, Venezuelan president Hugo Chávez told a group of journalists Nov. 19 that “[s]oon we won’t be talking about dollars anymore because the value of the dollar is in free fall and the dollar empire is collapsing.”

Chávez had just come from Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, where he had attended a meeting of OPEC. Venezuela and Iran proposed “de-dollarizing” crude oil operations at the meeting. The Saudi’s, not surprisingly, blocked the proposal and, reflecting their fear of setting off another run on the dollar, warned against even discussing such a thing.

Iranian president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad also appeared with Chávez at the press conference. “Fortunately, we are witnessing the fall of a system of arrogance (the United States) and continuing victories of the people,” he said.

Impact of dollar collapse

What if the dollar does collapse? Will it lead to the further decline of the “world tyranny” of U.S. imperialism?

The answer is yes.

- A collapse of the dollar would destroy the current international monetary system. No other country has the economic and military power to achieve world hegemony such as Great Britain enjoyed in the 19th century and the United States enjoyed in the mid-20th century. Therefore, no country or combination of countries can replace the dollar standard with a new system based on another currency, including the euro. The world would willy-nilly be forced back to some form of the gold standard and/or barter for international transactions, bringing about the collapse of the current credit system. Prices measured in gold, already in decline, would fall further. A dollar collapse would bring about hyperinflation in dollar terms but super-deflation in gold (real money) terms.

- A collapse of the dollar would destroy the very mechanism that has, as Fidel has explained, allowed the United States, using recycled dollars from China and other exporting countries, to finance the hardware and pay the other huge costs required to maintain a military machine more powerful than that of any other country, or any other combination of countries.

- A collapse of the dollar would mean that the United States could no longer run massive trade deficits with China and the oil-exporting countries, paying for consumer goods and oil with “perfumed paper bills” that then return to the United States in the form of purchases of U.S. Treasury securities. Instead, it would have to pay for imported goods like other countries largely do—with goods and services that it produces.

This is not a pretty picture, but it is the prospect we face on the economic and political fronts—leaving aside global warming and other potential catastrophes—if the anarchistic system of vulture capitalism isn’t replaced by a humane system of socialist planning in the not-too-distant future.

Meanwhile, U.S. workers and the middle class face a more immediate threat to their living conditions and livelihoods—stagflation. This is a term invented in the 1970s to describe an economic period like that decade, marked by falling or stagnant employment and rising prices measured in depreciating paper money.

In view of the worsening housing and subprime mortgage crisis, which has spread to the banking and credit system, a new stagflation crisis may be imminent. That, in turn, could set off a new run on the dollar. On the other hand, a run on the dollar could force the Federal Reserve to take credit-tightening measures that would deepen further the housing and financial crisis.