Boston’s government is sweeping the city’s homelessness crisis under the rug with a new ordinance designed to displace homeless people by force.

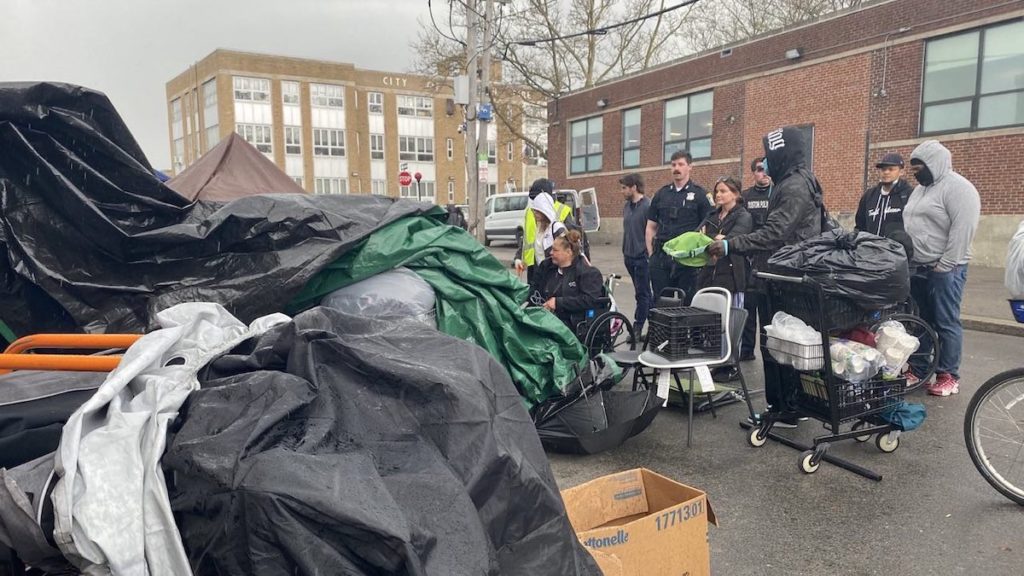

This ordinance, filed by Mayor Wu on August 28, follows the recent closure of the 100-bed Roundhouse Hotel. The Roundhouse was a major part of Mayor Michelle Wu’s initiative to address the growing encampment of homeless people on Atkinson Street and the nearby intersection of Massachusetts Avenue and Melnea Cass Boulevard, also known as “Mass and Cass.”

Wu administration returns to failed approaches

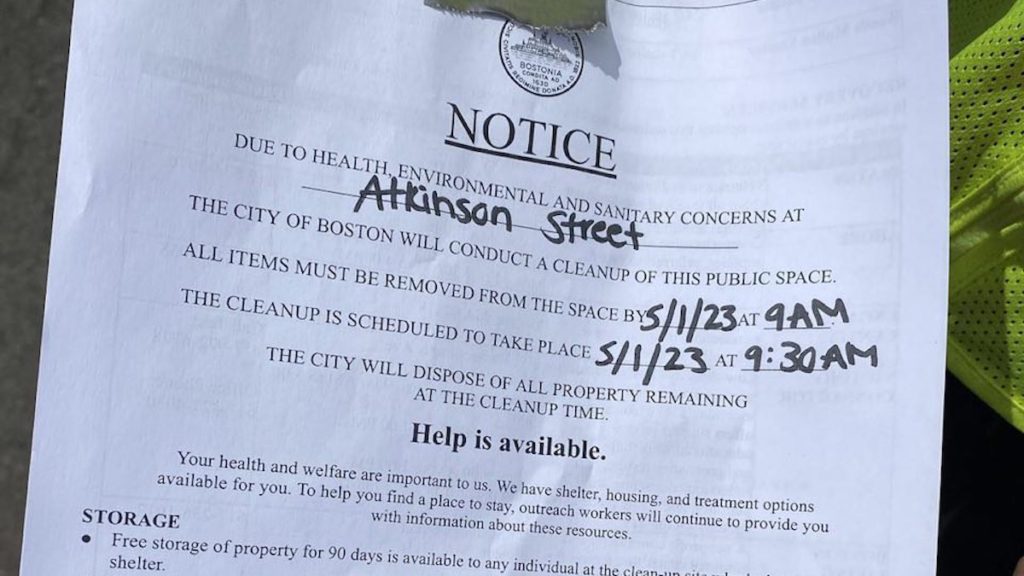

Wu’s proclamation that her approach is “not a return to the failed strategies of sweeps” is false. The ordinance establishes a “prohibition against unsanctioned camping with a tent, tarp, or similar temporary structure on public property.” It states that “the Boston Police Department will coordinate these efforts and will have a presence in the area at all times.”

The use of police and security units to surveil, harass and arrest those living on Atkinson Street is already having fatal consequences. “Because of the sweeps, I’m not getting to engage with patients I’ve known for more than three years,” said Noemi Guevara, an HIV PreP Navigator working with high-risk patients in the Mass and Cass area. “I don’t know how they’re doing or if they’re even alive.”

Temporary measures are a drop in the bucket

Boston’s 2023 Homeless Census counted around 5,200 people living without shelter, a 17.2% increase from 2022. The cost of living in Boston has grown out of control and working and poor people bear the brunt of commodified housing. The city has no real solution for this growing crisis.

The city plans to build a recovery campus on Long Island, Massachusetts, and rebuild the Long Island Bridge, which displaced hundreds of people when it was taken down in 2014. This project will take a minimum of four years to complete.

In the meantime, the city plans to open 30 temporary transitional beds on the Boston Public Health Commission’s campus. This is a drop in the bucket compared to the scale of the crisis. And when funding for these temporary sites inevitably runs out, people will have nowhere to go but the streets.

“The city is coming up with things that don’t have substance. They may fix a problem for a bit, but ultimately we’ll keep running into the same issues,” said Guevara. “It’s not getting to the root cause of homelessness and why people are using drugs. It’s embarrassing that we’ve only come up with 30 beds when we’ve lost so many, a whole building, and we have thousands of homeless folks outside. It feels disrespectful.”

Boston needs a proven housing-first solution to the homelessness crisis

On Sept. 1, four Boston City Councilors wrote a letter calling upon the Boston Public Health Commission to declare a state of emergency in response to the crisis at Mass and Cass. This letter, which asserts it is written “with a sense of urgency,” provides no specific proposals to mitigate the underlying issues.

Census data from 2020 showed nearly 22,000 vacant housing units in Boston that could immediately be used to house people, yet the city is not promising to provide anyone sleeping outside with dignified, permanent housing — the only solution with any hope of working. A truly urgent response to this crisis would start by securing housing for everyone.

A housing-first solution to the homelessness crisis is not a pie-in-the-sky fantasy. It has already been proven to work.

In 2007, Finland — another capitalist country with commodified housing — launched a Housing-First campaign that has dramatically reduced its homeless population. From 2007 to 2021, Finland cut its homeless population in half from roughly 8,000 to 4,000. Homeless people were provided housing as the first step towards a road of stability. This is the opposite of Boston’s “Continuum of Care” model under which secure permanent housing is typically provided only after certain conditions of mental health or addiction recovery have been met. Under this model, housing is treated as a reward instead of a foundational pillar of security.

Cuba, a socialist country, provides an even more inspiring example. Cuba’s Urban Reform Law transformed 85% of the country into homeowners and put the remaining 15% on the path to homeownership. Cuban renters cannot be charged more than 10% of their income in rent. Cuba also provides free comprehensive health care and cheap addiction recovery services to all residents. As a result, homelessness is essentially nonexistent, and only 0.08% of deaths in Cuba are due to drug use, nearly 35 times lower than in the United States.

No one should have to prove they are worthy of housing, which is a human right that everyone is entitled to. Boston needs a system that treats working people with dignity and sees housing as a necessity — a socialist system. “I knew housing in Boston was bad, but it wasn’t until I became a case manager that I realized how long some of these people have been actively doing the right thing and the system continues to fail them,” said Guevara. “It’s hard to make a system that isn’t built for you work for you.”