This article is part of Liberation’s commemoration of Black History Month, 2021.

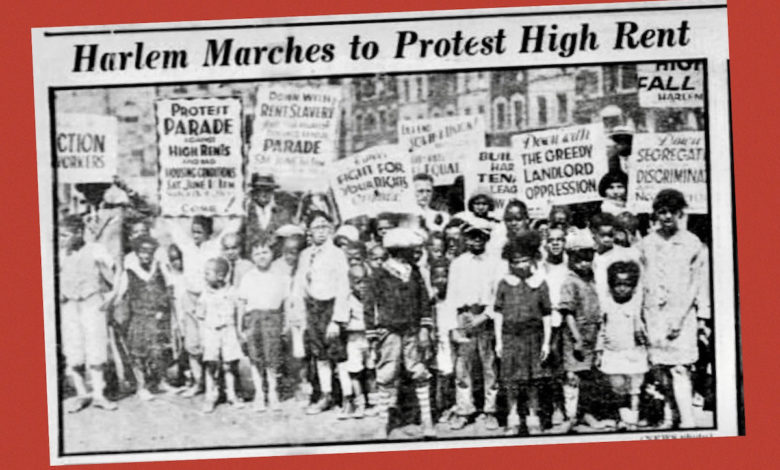

The housing struggle in Harlem during the Great Depression took New York City by storm, as some of the most oppressed sectors of society united and stood tall in the face of exploitation. Their resistance won major gains and taught future activists mass-action tactics that are still relevant in a winning strategy for change.

The Great Migration saw more than a million-and-a-half Black people flee the Klan-ridden, destitute South for better opportunities in Northern industrial jobs. Harlem became a prime destination. Due to segregation, Black people were relegated to live in pre-designated areas where landlords took advantage by charging exorbitant rents in comparison to what was charged white immigrant communities.

Communist Party and the Harlem Tenants League

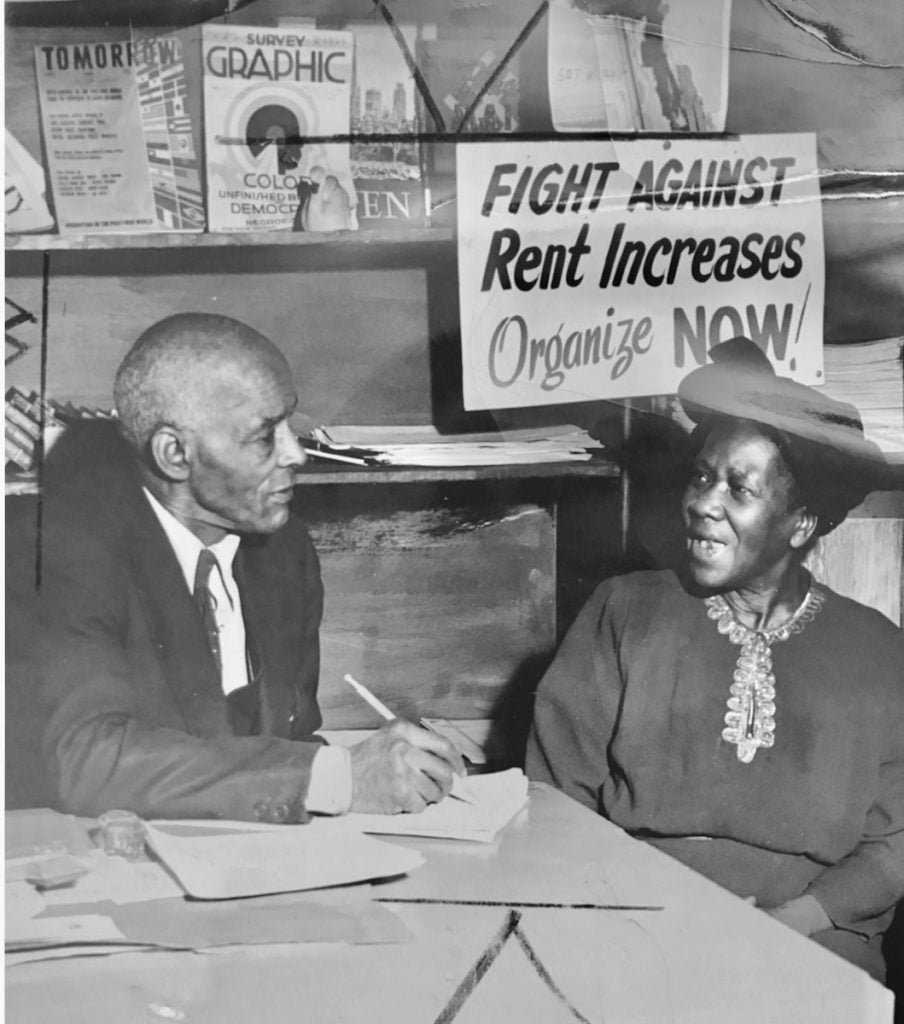

The Harlem Tenants League laid the foundation for militant mass action in Black communities for substantive change against racist rent hikes. The League was formed in 1929 at the suggestion of Richard Moore, a Black member of the Communist Party. Moore was to be elected the League’s first president. “The capitalist caste system,” Moore wrote, “which segregates Negro workers into Jim Crow districts makes these doubly exploited black workers the special prey of rent gougers. Black and white landlords and real estate agents take advantage of this segregation to squeeze the last nickel out of the Negro working class who are penned in the black ghetto. Rents in Negro Harlem are already often double and sometimes triple those in other sections of the city.”

The Communist Party played a major role in both the Harlem Tenants League and the Unemployment Council, another significant organization of that period. The multi-national CP prepared itself to do neighborhood organizing. It raised consciousness among European immigrant members living in Harlem on the urgent need to fight systemic racism, the absolute necessity of rooting out any racism or backwardness within its ranks, and the need to be in full solidarity with both the Black communities and its Black members.

The CP became known by Black Harlem residents and gained respect when it initiated a national campaign to free the Scottsboro Boys, nine Black teenagers falsely charged with raping a white woman in Alabama in 1931. For example, a CP-initiated Harlem rally that year demanding freedom for the Scottsboro defendants and an end to legal lynching began with a few hundred mostly white members, but swelled to several thousands as Black people joined it in the streets because the issue was of vital concern.

Segregation and high rents

The Harlem Tenant League’s initial organizers recognized that the rising rents in Harlem had become an inherent feature of segregation. The League decided to take action by holding protest meetings, organizing marches and strategically interrupting rent-law proceedings to galvanize community support. They organized rent strikes to resist rent increases. This tactic, although at the time new and unfamiliar to many, would evolve as the cornerstone of collective tenant activism during the Depression.

The most comprehensive gain the League helped win was more favorable tenant laws. The Civil Practice Act included both the Rivers and Perkins bills which addressed poor living conditions and rent increase protection; these bills were the earlier forms of New York City tenant laws.

1934 Harlem rent strike

By the onset of the Depression the Black community was especially ravished by unemployment with rates hitting 65%. The Harlem Tenants League had gained popularity in the community as it became a community support program that aided Harlemites against eviction. It helped create a culture of support and taught community members practical support skills like organizing rent parties and pressuring government agencies to support struggling Harlemites.

The Depression raised class consciousness, and the political and organizational influence of the Harlem Tenants League was felt in the Harlem rent strike of 1934. The first building to go on strike was a modern elevator building on Edgecombe Avenue in the “Sugar Hill” area, which had became increasingly popular for middle-class Black people in the formerly all-white neighborhood. But the new Black residents were subjected to sharp increases in rents with maintenance quality suffering tremendously. Enraged by the racist landlords, other Edgecombe Ave. tenants banded together and joined the rent strike and picket lines to protest high rents and poor conditions. Victories were won in all the organized buildings.

Another significant strike that year was among the tenants of Knickerbocker Village on the Lower East Side which produced the Knickerbocker Village Tenants Association. Both strikes played prominent roles in popularizing mass action housing reform.

Harlem Unemployment Council battles evictions

The Harlem Tenants League remained primarily a community support program. As the Depression raged on, there was clearly a need for other kinds of organizations more deeply embedded in the grassroots. The CP initiated Unemployment Councils, mass organizations which, while led by communists, were open for all to join. The Councils developed significant roots within the community.

One of the major tactics of the Harlem Unemployed Council was eviction resistance, sometimes organizing whole neighborhoods to stop evictions in progress. They frequently organized sit-ins, demonstrations and disruptions of government home relief bureaus. Their actions spurred mass support within the community, as they often won immediate reforms to alleviate desperate Harlemites.

Harlem’s Unemployment Council stood as an example, and sparked rebellion and action as other communities took notice and adapted their own tactics. In the Bronx, tenants became so emboldened by solidarity that when a marshal would come to evict a tenant it became common practice for the community to band together and return their items back inside the home. The city paid the marshals for individual evictions; as a result of this resistance in some instances the marshals were repeatedly sent back to unsuccessfully attempt the same eviction, making them too expensive. So people won the right to stay in their apartments.

If the city tried to intimidate the community with a large police presence, many communities did not hesitate to come together and fight back. In the Bronx, there were sometimes as many as 4,000 militants in the streets and on buildings, resisting the police and demanding the right to a home. Most were women. They threw hot water down on the police from buildings, threw marbles under the feet of police horses, or stuck the horses with the long needles used by hat makers.

The movement was national. In Chicago, when three Black communist organizers were killed in 1931 by police during one of these “rent riots,” 50,000 people took the streets in a memorial march.

Comparisons with conditions today

The heroism of the Black Harlem masses was rooted not only in the economic implosion of the Depression era but also in the fact that, while housing is a basic human right, landlords sought to exploit suffering for profit.

Today the COVID-19 pandemic has made even clearer the inability of the system to put people above profit. Some 78 million claims for unemployment were filed in the last year due to the government’s mishandling of the pandemic. With so many unable to pay rent, there is the possibility of thousands or even millions of evictions once the eviction moratorium is lifted, yet rents have not been canceled. The White House reports that as of 2019, over half a million people were homeless while almost 17 million potential homes were empty, warehoused by landlords to keep profits high.

Much as the struggles in the 1930s exposed the role of the police, the Movement for Black Lives uprising over the summer of 2020 sparked a mass rebellion that tied in the fight against killer cops and police brutality.

Pickets, marches, rent strikes, creating organizations and building localized pressure campaigns are the order of the day just as they were in the 1930s. The organizers in Harlem and elsewhere have taught us that the power lies with the people coming together and it is possible to win. For the Harlem community, it was a struggle for reform, but the most necessary element was the struggle for liberation.

Today, the Black struggle still leads the way in the fight for housing and the fight against all forms of oppression. Let us take note, and build a movement, not just against the forms of oppression by themselves, but a movement against the whole capitalist system which benefits from such vile exploitation.