Wounded Knee, South Dakota, is the site of the infamous Dec. 29, 1890, massacre of 300

defenseless Native men, women and children by the U.S. Army 7th Calvary. Members of the

Lakota nation were rounded up and forced into a gully as soldiers fired from four rapid-fire

Hotchkiss guns, killing them all.

But Wounded Knee is also where the Lakota people and American Indian Movement leaders

took a stand on Feb. 28, 1973, in an historic takeover which lasted 71 days. Surrounded and

massively outgunned by the U.S. army, the Wounded Knee warriors courageously resisted as

they presented demands for justice and respect for Native treaties.

From Feb. 24 to 28 of this year, hundreds of Oglala Lakota and supporters came together in the

towns of Rapid City and on the reservation, Porcupine, Manderson, Wanblee, Kyle and

Wounded Knee to mark the 50th anniversary of the takeover and to commemorate it.

They came to honor the sacrifice of the 1890 martyrs, the heroes and martyrs of 1973, and to celebrate their ongoing fight for justice. Workshops, pop wows and film showings were held. Wounded Knee veterans related their stories of bravery amidst hundreds of thousands of rounds fired by the U.S. army. The women of Wounded Knee were especially honored.

Bill Means, longtime leader of the American Indian Movement, told hundreds of people gathered at this weekend’s four-day event the reason for the occupation: “Remember, we came here for the 1868 Ft. Laramie Treaty. We didn’t come here just to raise hell. We had to make a statement, to tell the world that Indians are still alive, that this is still our land and the Black Hills are not for sale!”

U.S. violates own treaty, steals Black Hills from Indigenous people

The pine-forested Black Hills of 1.2 million acres have been in dispute ever since the U.S.

cancelled the 1868 Ft. Laramie Treaty, which had guaranteed the land west of the Missouri

River — over half of today’s South Dakota — “in absolute and undisturbed use and occupation of

the Indians.” It was called The Great Sioux Reservation.

But six years later, gold was discovered in the Black Hills by an expeditionary party organized by

the infamous Gen. George Armstrong Custer. A gold rush brought thousands of white miners to

invade the Black Hills. The U.S. laid claim to the Black Hills and surrounding lands and the Great

Sioux War of 1876 began. By war’s end, the Black Hills — sacred to the original peoples — were

stolen. The promised land of the treaty’s Native signers was reduced to a fraction, and on the

least productive land.

Although the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 1980 that the Black Hills were indeed taken illegally

by the government, it nevertheless refused to rule for its return to the original inhabitants. The

pittance of a monetary settlement awarded by the court has long been rejected with an enduring slogan, “The Black Hills (Paha Sapa in Lakota) are not for sale!”

The 1973 battle was a clarion call that drew widespread support from other Native nations along with non-Native activists. The militancy of AIM and the Lakota resistance instilled a great Indigenous pride that reached far beyond Wounded Knee.

Participants in 1973 takeover speak

Vina White Hawk held her two-year-old grandson as she waited with her 90-year-old mother Bernice to see the young horse riders join up for the final walk to Wounded Knee. She described how she and others brought food, blankets and ammunition under the very noses of the U.S. army during the 1973 siege.

“We were members of American Indian Movement since before ’73. My mother was really feisty at the time.” Pointing, she said, “She brought us to the turnoff down that road. Then she went to the government roadblock, spinning the wheels of her car, making noise, honking the horn and then she took off. The cops chased her down the road, while us guys went into the woods and into Wounded Knee, bringing everything we could.”

The U.S. government tried to wipe out Native nations, robbed them of the land and economic subsistence, banned traditional ways, culture, language and religion. The genocidal wars and removals took an incalculable toll. Tens of thousands of children were kidnapped and taken to brutal “Indian schools” meant to destroy their identity.

By the 1960s, an Indian Pride movement began to rise, inspired by the Black civil rights and liberation movements. The 1968 birth of AIM against police brutality in Minneapolis, the Alcatraz takeover, protests at Plymouth Rock, one struggle inspired another.

At Pine Ridge reservation, South Dakota, it all came to a head in the early 1970s. Compounding the longstanding poverty and suffering was the tribal administration of chairman Dick Wilson. He had formed the notoriously violent GOON Squad (‘Guardians of the Oglala Nation’), to maintain his power and control over the tribe’s resources. The “traditionals,” part of the Pine Ridge community that had opposed Wilson, came under attack.

The occupation ‘changed the way Native people live in this country’

They asked AIM to help defend the people. Carter Camp, noted AIM leader and Ponca from Oklahoma, helped lead the takeover. Dennis Banks, Anishnaabe, and Clyde Bellecourt, Lakota, were AIM’s co-founders. They answered the call. Russell Means, Oglala from Pine Ridge, and Banks became the main spokespersons of the takeover. When the Wounded Knee occupation ended in May 1973, Banks and Means were indicted, facing years in prison. The judge later dropped the charges due to massive government misconduct.

Vic Camp, son of Carter Camp, reflected during this weekend’s events: “Wounded Knee to me is

a very sacred place. If it wasn’t for Wounded Knee, a lot of us wouldn’t be here. A lot of us wouldn’t be able to practice our way of life, speak our language, to be proud of who we are. We could wear our braids, we could have our ceremonies out in the open. Wounded Knee changed the way Native people live in America.”

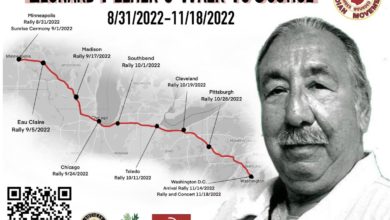

Action demands freedom for Leonard Peltier

Prominent during the four days was the demand for Leonard Peltier’s freedom. He is still in federal prison going on 48 years, a victim of FBI and U.S. persecution for having defended Pine Ridge elders and youth from murderous violence perpetrated by Wilson’s GOON Squad. In the months after the end of the Wounded Knee takeover, 64 people were murdered on the reservation, part of Wilson’s retribution. AIM members, including Peltier, came to protect the people when the U.S. ignored their pleas. The complete history is related in the documentary, Incident at Oglala. A clemency appeal is on President Biden’s desk, backed by many thousands of supporters.

Youth lead march, mark seventh generation in the struggle

Large numbers of youth took part. Many come from the original families of the 1973 action and

are being raised in Lakota pride, culture and history. They led the “horse nation” into Wounded Knee, took part in the march, the pow wows, songs and drumming. They held high the AIM flag and sang the AIM song.

Camp addressed the youth on the walk: “I want to thank all of our relatives, all our youth for coming and leading us to Wounded Knee. You are the seventh generation. It’s your time to stand up and protect your water, defend your land. Remember your treaty rights, protect those treaties. Our treaties are the only thing that holds up to United States Constitution. It’s the supreme law of the land and we have to remind the United States government that this is our land.”

Main photo: Aim leader Bill Means (center, in black hat) addressing closing rally. Liberation photo