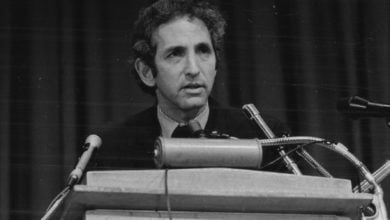

Geronimo Ji Jaga

Pratt, noted Black revolutionary who fought a 27-year battle for

freedom after an FBI

frame-up, died at his home in Tanzania on June 3 at the age of 63

due to illness.

He had been

living in Tanzania for several years, after his hard-won release

from California prison in 1997.

Geronimo was born

Elmer Gerard Pratt on Sept. 13, 1947, the youngest of seven children.

He grew up in rural Louisiana, Morgan City, during the era of

segregation. Ku

Klux Klan attacks

on the Black community were common.

Geronimo’s

consciousness was shaped in early life by the brutal racism of the

South. Early on, his family and community instilled in him an

understanding of the need for community self-defense against racist

attack. He was deeply affected as a 15-year-old when his brother

Timothy was viciously beaten by Ku

Klux Klan members.

Geronimo and his

three brothers worked hard alongside their father Jack, collecting

scrap metal to sell in New Orleans. In the biography

“Last Man Standing: The Tragedy and Triumph of Geronimo

Pratt”

by Jack Olsen, Geronimo recounted: “Daddy taught us to be tough … me and my brothers, we

worked in that fire and smoke till we near dropped, baled up rope,

rags, newspapers, ripped the lead plates out of batteries, raked hot

ashes for coat hangers and wire springs and bolts. … We could break

the welds and chop up a car in an hour…”

When his father

suffered a debilitating stroke, it was now upon his mother Eunice and the

children to keep the family going. It is a tribute to the parents’

determination that all the children went to college.

Deacons for

Defense

Geronimo’s life

took a different turn at the age of 17. The elders in the African

American community led an organization called Deacons

for Defense and Justice.

They quietly but effectively organized self-defense of their

community.

After another

killing by Klansmen, the elders called on Geronimo and other youth to

join the U.S. military. Their training would help defend the

community on their return. Geronimo said, “By the time the elders

finished amping me up, I was ready to take on the whole KKK

single-handed.” (Last Man

Standing, p. 26)

The next day he

took a bus to join the army.

Geronimo served

two tours in Vietnam. He was wounded twice and awarded two purple

hearts. His war injuries would haunt him in prison, where extremely

harsh conditions made his physical suffering greater. It was on his

second tour that he became conscious of the genocidal and racist

nature of the war.

With his

discharge from the military in the summer of 1968, the elders sent

him to Los Angeles to meet the Black

Panther Party

for Self-Defense. Geronimo quickly met BPP leader Alprentice “Bunchy”

Carter,

who educated him in revolutionary politics, and gave him the name

Geronimo Ji Jaga.

Carter in turn

recognized Geronimo’s abilities. He was exceptional for his keen

defense and discipline skills, forged in his childhood and U.S.

military training, as well as a deep sense of justice.

Defense

minister for Black Panther Party

Geronimo’s

effective role as defense minister in the Los Angeles Black Panther

Party made him a major target—with other BPP members—for

repression by the FBI’s secret “Counterintelligence Program”

(COINTELPRO).

The fascistic FBI director J.

Edgar Hoover

had declared the Black

Panthers to be “the greatest threat to the internal security of the

country” and called on agents to “submit imaginative and

hard-hitting counterintelligence measures aimed at crippling the

BPP.”

Beginning in 1968

in Los Angeles, the LAPD

and FBI launched a war against the Black Panthers, both open and

covert. Their strategy included assassinations, armed raids on BPP

offices and subversive campaigns to turn radicals against each

other. This was repeated in cities from Chicago to Newark to New York

City to Oakland.

In a major LAPD

raid on the Panther’s Los Angeles headquarters on Dec. 8, 1969, dozens of LAPD

cops fired 5,000 rounds into the building. After hours of gunfire,

six Panther members were wounded. Casualties were minimized because

for weeks Geronimo had mobilized the members to fortify the offices

with walls of sandbags.

At the same time,

cops broke into Geronimo’s apartment and fired into his bedroom.

The attack mirrored the assassination of BPP leaders Fred

Hampton and Mark Clark by Chicago police only four days earlier.

Failing in their

attack, the FBI and LAPD then manufactured an indictment for murder

against Geronimo.

Framed for

murder

One year earlier

on the evening of Dec. 18, 1968, a woman named Caroline Olsen and her

husband Kenneth were shot in a tennis court during an apparent

robbery in Santa Monica. Caroline Olsen died 11 days later.

With false

information from BPP member Julius Butler—who was revealed years

later as an FBI informant and close collaborator—Geronimo was

arrested and charged with first-degree murder. At the time of the

murder, Geronimo was in Oakland at a BPP meeting, and the FBI, which

had the Los Angeles and Oakland offices under constant surveillance

and wiretapping, was fully aware of this fact. The FBI had

successfully exploited growing divisions and manufactured others inside of the BPP so that witnesses

who were with Geronimo refused to testify on his behalf.

Because of FBI

and LAPD falsification—and the COINTELPRO operation unknown to

anyone at the time—Geronimo was convicted. The trial included false

testimony against Geronimo based on lies told by the FBI informer. For

27

long years—including eight years in solidarity confinement—Geronimo

suffered the brutality of prison, demonization and a long chain of

frustrated appeals and parole denials.

It took many

years and the tireless work of appeals attorney Stuart

Hanlon,

along with trial lawyer Johnnie

Cochran,

before Geronimo was finally freed.

In a rare

occurrence, the FBI and LAPD had to pay a $4.5 million settlement for

his wrongful conviction. But no amount of money could make up for the

years Geronimo lost and his suffering at the hands of the state.

Bato Talamantez,

former political

prisoner

of the San Quentin Six struggle, was a close friend of Geronimo. “Ji,

like George Jackson, was a great bridge of love and solidarity

between prison racial groups, trying to bring about unity so they

could win justice for everyone.

“He continued

to care greatly about serving the Black community, in Morgan City or

Tanzania. Ji confided to me many times, and he told me again last

month after his visit to the U.S., ‘I’m going back across the

waters … to Mother Africa.’”

Attorney Stuart

Hanlon said: “Geromino was much more than a client. From

the very beginning he was a close friend. What I will remember

most about him is his warmth, his joy at life, his lack of bitterness

at those who framed him and took away 27 years of freedom. I will

also remember his indomitable will and strength, his refusal to yield

or bow to oppression and fear. He often told me they locked him in

the hole for nine years but never could take away his freedom,

the freedom of his mind and soul to soar and be always with his

comrades and his ancestors.

“The

Government could never silence him or his voice. Before his false

imprisonment, during and after, his voice rang true for justice and

freedom, for the end to racial and all forms of oppression. While in

prison and for the 14 years outside that he had after his release, he

was relentless in fighting for these beliefs. He was, and is a true

warrior and leader. I will miss my friend, and we will all miss the

power and commitment of the warrior Geronimo Ji Jaga.”