Skip to a section:

- The prison house of nations

- Dawning of a new era

- Socialism against oppression

- Challenging changes

- Towards a socialist future

The past, as they say, is never truly past. In recent months, Soviet nationality policy, a topic many thought consigned to academic backwaters and communist happy hours, has been thrust into the forefront of public conversation. The war raging in Ukraine has brought to the forefront questions about the borders, languages, and ethnicities of the country. How did they get that way, who is responsible, and how do these questions impact the causes and consequences of the current crisis?

The conversation, however, has been something of a battle of dueling nationalisms. In response to far-right Ukrainian nationalism, Russian President Vladimir Putin has spun his own nationalist views, blaming the Bolsheviks for setting the stage for tensions between Russia and Ukraine today.

Taking the two sets of critiques, one might be led to believe that the Soviet Union was some sort of venal, brutal empire that held the just aspirations of its various nationalities and ethnicities captive, manipulating “national borders” to generate fake nations and false national consciousness.

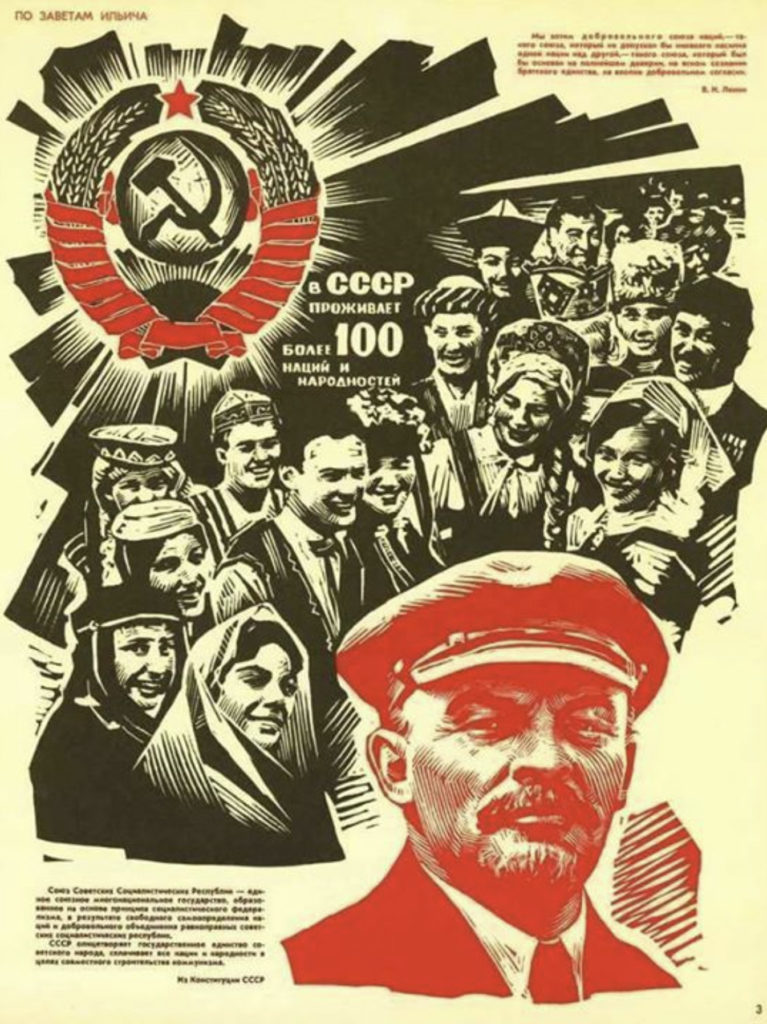

The truth is far from the stories told by both the Ukrainian nationalists and Putin. The Soviet Union was the most advanced attempt at addressing national oppression, racism and discrimination at a country-wide level. Among many other things, the USSR was the first nation to engage in widespread affirmative action at levels no country before or since has reached.

The Soviets took hundreds of nationalities and brought them under one governmental authority that took on economic backwardness and cultural repression to open up a liberatory future for peoples who had spent centuries under the yoke of the Tsars’ imperial ambitions.

In fact, the depth of the tragedy afflicting Eastern Europe right now can only be fully understood in light of the decades-long Soviet effort to put an end to national antagonism and forge a future based on the unity of working and poor people for their collective benefit and that of humanity.

The prison house of nations

The Tsarist empire was known, in certain circles, as “the prison house of nations.” From the 11th to the 19th century the various Tsars from Ivan the Terrible to Catherine (and Peter) the Great, took control of a vast territory stretching from the Pacific into Central Europe and from the Arctic Circle to the Black Sea and Central Asian steppe. Under its banners fell nearly 200 nationalities and ethnicities and a veritable Tower of Babel of languages.

Across all nations, exploitation and inequality were rampant. Ninety percent of non-Russian peoples across the empire were illiterate — 75% of Russians were in the same situation. In an effort to create a successful divide and rule strategy, the Tsarist autocracy reserved higher education for the more privileged group of Russians, meaning most doctors, teachers and other professionals in the oppressed nationality regions were almost exclusively Russian. In Bashkiria, nestled between the Volga and the Urals, only 10 of the over four thousand secondary students were Bashkirs. In major cities, oppressed nationalities filled the ranks of the lowest paid workers. It was once said that every “shoe black” in Moscow was from the Caucasus region and that one-third of all Tatars were janitors, porters and “rag pickers.”1

The Tsars used land grants and colonization on the lands of oppressed nations by Russians as part of a broader effort of “Russification” designed to eliminate national languages and cultures. For instance, Karelians speak a language close to Finnish, but selling a bible in Finnish was punishable by exile and schoolchildren were forbidden from speaking Karelian. The deeply anti-semitic rulers deployed a KKK-style regime of terror against Jews, known as the Black Hundreds, whose murderous rampages were so notorious the term “pogrom” became known across the world. Ghettos were the norm in many of the cities and towns as the various nationalities were shunted into Russia’s developing capitalist enclaves.

Opposition to ethnic and religious intermarriage also went along with the official racism and bigotry. In addition, the Tsars were not above pitting various nationalities against one another over land and economic opportunities. National oppression, then, was also multi-layered, with some ethnic groups also oppressing others while still facing great Russian chauvinism.

This created a unique oppositional culture, particularly among communists. There were radical nationalists, representing the desire of national elites for economic supremacy in their own territory, connecting “liberation” to formal independence. There were socialists who believed nationalist antagonisms to be of secondary importance, stressing the unity of all workers against the Tsarist ruling class. There were other types of socialists and communists who believed that radicals should organize based on nationality, and by extension, in federations of nationalities. And then there were the Bolsheviks, who preached multinational unity of workers and peasants against the Tsar and the ruling capitalists and landlords — while also placing extensive focus on militant opposition to all forms of national oppression and bigotry.

Their overall approach was rooted in an understanding of national oppression as an outgrowth of capitalism and imperialism. The process of gobbling up nations by Tsars was linked to a hunger for land, resources and labor to grow their riches and compete with other imperial forces seeking the same.

Their main conclusion was that it would never be possible to build a coalition of the oppressed and exploited, and overthrow the rulers, without foregrounding that true liberation required total destruction of national oppression and replacing capitalism. As such, a major part of the Bolshevik program was “the right of nations to self-determination.” While stressing, as communists always have, that socialism and communism require multinational unity transcending the national borders set up by rival capitalists, they stated that their commitment to national liberation was such that if secession was what it took for oppressed people to feel free, they would support it. These would be the basic principles that would help bring them to power, and provide the foundation for the Soviet approach to nationalities.

Dawning of a new era

Following the 1917 revolution, addressing national oppression was among many deeply complex challenges: ending participation in WWI, feeding the starving population and redividing the great estates among the peasants. This was all happening in the context of extreme hostility from imperialism. Fourteen capitalist nations sent troops to try to, as Winston Churchill would later say, “strangle Bolshevism at its birth.” The same nations also sent arms, gold and other equipment of war to every would-be ruler — as long as they hated communism.

This immediately created a new set of issues as it concerns nationalities, principally that (as the Bolsheviks had long noted) the national struggle and the class struggle were intertwined. This meant that it quickly became weaponized by various forces looking to overthrow Soviet power.

Further complicating matters was the fact that the conglomeration of ethnicities and peoples, emerging as they did from the pre-capitalist world, rarely had a clear history of “national borders.” Meaning that the struggles kicked off by the 1917 revolution were as much about defining (and debating) the relationship between language, culture, religion and territory as resolving them. Many struggles for “national liberation” in the post-1917 period were also struggles over how a given area should be governed, and whether that was better done as formally independent states or a part of a broader Soviet federation uniting the various nations into a socialist project.

This led to a complex set of events that cannot be fully summarized here, but essentially boiled down to divisions between elements of oppressed nations who preferred to “go-it-alone” in alliance with imperialist powers and Tsarist revivalists, and those already part of the Bolshevik movement or attracted by it’s “anti-racist” and pro-poor policies. In most cases these issues were settled by force of arms.

This led to a range of different struggles, between nationalists and communists (Ukraine), communists and nationalists vs. feudal lords (Bukhara), Bolsheviks vs. Mensheviks (Georgia) and just about everything in between. At the end, tens of millions of non-Russian peoples attached their homelands to the broader socialist federation that was the USSR.

By the mid-1920s the “shape” of the USSR, until Word War Two, was set — most of the Tsarist empire minus the Baltic states and elements of the western republics that went to various Central European empires. The next decade or so would be a time of experimentation, followed by a consolidation of the overall model that would remain for the rest of the Soviet period.

Socialism against oppression

Facing underdevelopment, lack of resources and without a roadmap, the Soviet leadership nonetheless set out to try to rapidly address the challenges of centuries of national oppression. Soviet policy emphasized supporting self-determining “national forms” that were also calibrated to exist within the broader framework of socialist construction. This process wasn’t without contradiction.

A socialist project is tasked with marshaling the resources of society in order to meet its democratically-determined collective needs and wants. But in the context of deep underdevelopment, almost everything becomes a trade-off. Do you build a bridge or a dam? And where? If illiteracy is high, but you only have the resources for so many schools, teachers and books, who gets priority? In other words, the dilemma was how to balance overall improvement in collective wellbeing while also closing the differential gaps between oppressed nations — all at varying levels of development/underdevelopment.

Over the years of the Soviet Union’s existence these issues were never fully resolved, but the core elements of the Soviet approach were: the creation of national territories, promoting national languages and cultures, and extensive affirmative action policies. Emphases on various aspects of these policies varied over time and across space, but generally held true and reflected the broader goals of the revolution to lift up the overall standard of living, while also significantly integrating oppressed nationalities, particularly into the scientific-technical intelligentsia.

As one study of the issue from 1991 noted: “the growth of mobility opportunities has been the highest among nationalities with the lowest levels of socio-economic attainment.”2

For instance, by 1975, Jews, Georgians, Armenians, Estonians, and Azeris were the top five ethnic groups as it concerned “specialists with a higher education.”3 As the table below reflects, the equalization over time speaks to Soviet priorities.4

Relatedly, in 1970, the top six nationalities in terms of enrollment in higher education were: Estonian, Georgian, Lithuanian, Latvian, Russian and Kazhak. In Soviet Central Asia, what had been arguably the most undeveloped part of the Tsarist empire, by 1982 there were more doctors per population than any non-communist country except Israel and more college students per population than Japan, plus a higher proportion of women.5 In the Soviet Arctic the first real educational system was set-up by the 1930s and by 1975 in the Chukchi National Territory 99.1% of all Indigenous children were enrolled in school through high school.6

In 1978, there was one Indigenous doctor per every 1,000 people, the same year in the United States, there was only one Indigenous doctor for every 16,000 people.7 In Moldavia, before World War Two, there was one person with a PhD — by the early ‘80s there were 2,200. Moldavians increased 110% in professional and paraprofessional occupations between 1959 and 1973.8 Similarly, from 1950 to 1975 in the 14 non-Russian “Union republics” (Kazakhstan, Georgia etc.), the annual growth of scientific workers was 54% higher than among Russians.

The largest three nationalities in the USSR were — by a significant margin — Russians, Ukranians and Belorussians. By the 1960s all three were underrepresented in the Supreme Soviet — the main national legislative body – while Uzbeks, Georgians, Tajiks, Azeris, Armenians, Kirzighs, Turkmens, Latvians, Estonians, Lithuianians and Komis, among others, were all overrepresented.

One examination of the 1989 Soviet budget noted that government policy trended towards the redistributive principle, relaying how in 1989 the budget “transfers funds from more developed to less developed republics,” and further, “less developed republics have received higher rates of investment than their level of economic development would predict. And per capita expenditures on health and educational programs have been relatively equal among republics.”10

In 1920, Azerbaijan imported almost all products except oil. By 1958, they were exporting 120 different industrial goods and produced per capita more electricity than Italy and France, more steel than Japan and Italy, plus they had a larger catch of fish than France.11

On top of that, the national legislature had two tiers. In addition to the Supreme Soviet, there was also the Soviet of Nationalities, which had to approve all legislation for it to become law. Even if this body was a “rubber stamp” as is often alleged, the general thrust of nationalities policy clearly reflects that the very existence of multiple layers of affirmative action, language access and social uplift reflect they were putting a rubber stamp on relatively anti-racist policies.

One writer relayed a story from an encounter — a conversation with a professor — of the Gagauz peoples of Moldavia (population 125,000 circa 1977) whose written alphabet was created in Soviet times. The professor noted:

“‘We have artists, we have composers, we have our own poets and writers: those who write on the basis of folk themes … and those who collect our folklore. Among scholars we have linguists and historians. The anthropology of the Gagauz is being studied … in Moscow we have Comrade Guboglo.’

The writer further relayed that:

“I admit, I was surprised to learn Guboglo was Gagauz; I had translated articles of his into English … so one of the Soviet Union’s leading anthropologists, a man who theorizes on matters far beyond the bounds of his own nationality, is a member of a people who did not even have an alphabet little more than 20 years ago.”12

The same author notes: “In Dagestan, a tumbled Soviet mountain vastness of only a million and a half people, northwest of Iran, school is presently taught in nine languages … USSR-wide instruction is in 52 distinct tongues.”13

In an effort to address the pervasive Russification in Ukraine, Soviet authorities pursued an aggressive effort at “linguistic Ukrainization” in the 1920s where literally hundreds of thousands of people were put through courses in Ukrainian. In 1923, 37% of newspapers were in the Ukrainian language, by 1928 63% were. Fifty-four percent of books printed in Ukraine were Ukrainian in 1928, 31% had been in 1923.14

In 1991, the Soviets held a referendum on whether to break up the country or not, notably for our purposes, the vote in Russia was lower than all of the oppressed nations where the referendum took place. In the Central Asian republics over 90% voted to keep the USSR together, for instance, as opposed to the 73% in Russia. Notably, the national regions within the Russian socialist republic mainly saw higher pro-Soviet percentages than Russia writ-large, with 9 out of 16 voting over 80% in favor of not breaking up the USSR.15

Another way to look at this is through the lens of historical memory. In 2013, Gallup polled people in some of the former Soviet republics asking them if they felt the break-up of the Union did more harm than good to their current country. Armenia, Kyrgyzstan, and Ukraine all had a larger percentage of those saying it caused more harm than good than Russia, with Tajikistan just 3% behind Russia.16

In 2005, a survey was done in Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan, asking people if they agreed or disagreed with the statement: “The Soviet government responded to citizens’ needs.” 82.4% of Kazakhstan agreed that the Soviet government did indeed respond to citizens’ needs. 87% of those in Kyrgyzstan felt similarly, 70.2% in Uzbekistan concurred.17

In a Reuters article from 2011, “Soviet nostalgia binds divergent CIS states,” a 46-year-old beauty salon owner from Kyrgyzstan told the newswire: “Maybe our wages weren’t that good, and I hated the ‘Iron Curtain’ most of all, but there was stability. There were the brotherly republics nearby, and you felt the shoulder of your neighbor.”18

In the same article, Saijon Artykov, a 67-year-old retired geologist, reflected that: “We had good wages and I bought an apartment in Dushanbe, Now we struggle … to survive.” Saying further that: “The Soviet Union gave me a first-class education, for which I did not pay.”19

Challenging changes

The varying contradictions of the Soviet model impacted heavily on the issue of nationality. Particularly bedeviling for the Soviets were issues of land, resource distribution and language. While “national impulses” were seen as natural, they were not seen as inherently good. As socialists, the Communist Party of the Soviet Union was looking to build an “internationalist” society in keeping with socialist values.

Marxism posits that nationalism is ultimately a creation of capitalism, the struggle of rising capitalists to create a consolidated, politically distinct territory to conduct their commerce. The process of marking off boundaries within which languages, cultures and natural features combine to create smoothly working systems of buying and selling with unified “weights and measures” (money, taxes, etc.) is the process of “nation-building.”

Socialism, and ultimately communism, seeks to transcend capitalism by, among other things, eliminating these artificial barriers to better facilitate the use of the deeply interlinked “world market” to democratically meet the needs and wants of the people — as opposed to serving the whims of profit reaped by a tiny handful as exists under capitalism.

The Soviets then viewed their task in erasing national oppression as a bridge to a multinational state embodying the broader socialist principles. So that meant having the essentially simultaneous imperatives of erasing national oppression, celebrating national cultures and situating them within a new “all-union” culture based on collective economic uplift of the working class and peasantry who now commanded the resources of society.

On the language front, this created some clear challenges. The brutal history of the Tsars had already made Russian the common language for the broader Soviet population. However, this “Russification” was imposed through the brutality of the tsarist economic churn. It also came with the chauvinist conception that Russian culture represented a “higher form of civilization” — related to modern, urban culture in which many working-class people were integrated into to some extent. This was an issue of greater import given that one major area where society leapt forward after the revolution was opening up the traditional cultural realms to millions locked out before by dint of class status.

This meant that even among oppressed nations there could be resistance to new language policies among urban workers in particular, who associated national languages with the rural and often reactionary culture of the peasants.

The USSR and the preceding empires covered a vast territory, and as mentioned earlier, Russians were often given land grants in which to settle by the Tsar among various oppressed peoples. This policy intentionally created a favored population of settlers who often held preferential tracts of land. This laid the basis for sharp conflict over who rightfully belonged where and who held political power. It also led to serious questions about land as a resource, and moving forward, who had a right to veto who lived where if it conflicted with development needs.

An issue which bled into the deeper point of how exactly to distribute limited resources was that the Soviet Union was racing to reach a level of at least rough parity with the West in many regards as a safeguard against invasion and overthrow by those same hostile powers. These would become the faultlines of nationality policy in the USSR. Ultimately they were all resolved by leaning more towards the “all-union” side of things, than the “national” side of things. This meant conciliating to a degree with the existing “all-union” elements, which were mainly leftovers from the forced semi-homogenization of the Tsar’s time.

On language, this meant ultimately a step back from ambitious efforts at requiring use of various national languages, more or less limiting them to where it was most feasible: elementary education, national cultural activities, which were expanded and promoted heavily, and where voluntary adoption was taken up. This meant Russian remained the dominant language of the Union, but that previously suppressed national languages were in frequent use.

This was obviously a major step forward from tsarist times, and led to a fuller flowering of many more languages than had ever been possible previously. However, it did tend to mean that “Russian” culture remained ascendant to a degree, remaining the main language in which the crucial social, economic and political affairs of the country were conducted. For instance, this meant it would be easier for Tchaikovsky to become popular in Tajikistan than for a Tajik opera to take off in Moscow. Although it also meant a hugely expanded scope for Tajik opera in Dushanbe.

From a land perspective, ultimately the contextual realities of the USSR favored a less modified status quo. Until 1927, the Soviets closed vast swaths of territory, especially in central Asia, from any sort of new settlement. This, however, became untenable based on considerations related to food, economic development and national security.

The basis for sovereignty in the modern imperialist world is ultimately control over what you eat. Nations that can’t feed themselves are always at a great disadvantage. Many national territories contained land far beyond what could conceivably be farmed by simply those already there. And, even in more dense rural settings, sometimes the most productive land was inhabited by settlers. Additionally, the Soviets, haltingly then in a forced march, wanted to change the structure of agriculture away from large estates and atomized small farms and replacing them with a cooperative and collective sector. The imperatives introduced by these various issues could easily collide.

Firstly, if the overall level of food production for the entire country could be raised by having more of X people in Y place, that is a strategic imperative — ensuring both development and equitable distribution — that might end up reinforcing demographic changes favoring one nationality over another. A similar issue might arise if, for instance, an area of Ukraine that is roughly 45% ethnically German, and prior to the revolution that population controlled 75% of the land, but during collectivization the Germans more rapidly adopted collective policies. That might mean that the position of the Germans on the best lands would continue. In the wake of WWII, the total destruction the Nazi war machine levelled against the USSR meant that the only way to really revive production was to “open up” new lands, which of course might also exacerbate historical tensions.

Or you might have a situation where a certain population close to a border or key natural resource where imperialist scheming represented a special danger to the broader national security of the USSR required special policies to ensure these issues were not exploited.

These various issues related to land use are the underpinning of many of the more brutal policies implemented against portions of or entire national populations in the Stalin era. Nationalist themes often became rallying points for various grievances and especially where they concerned perceived national security interests that resulted in collective punishments like mass deportations.

Without a doubt many of these actions are without justification, but they are often falsely represented as “anti-national” when nationality was really secondary. Peoples were targeted because they were seen as oppositional to a particular goal of the leadership.

On the resource front, it is true as some have noted that there was never any “official” mechanism to direct a specific percentage of national resources to oppressed nations. On the other hand, there was often one-off levies in yearly budgets to address these issues, and as the overall record shows, the general thrust of Soviet policy meant that investment in the various oppressed nations was often equal to or greater than those in Russia on a proportional basis. In fact, it’s widely noted by scholars that dissatisfaction among Russians that they were being disadvantaged as compared to various nationalities was a major factor in driving anti-Soviet sentiment.

Similarly, the general thrust towards equality paradoxically created more competition between newly empowered national elites over the still relatively scarce resources of the USSR. Ironically enough then, the very success of the Soviets in lessening national oppression started to create new tensions on national lines that contributed to the Soviet collapse.

All of the various issues mentioned here of course merit fuller discussion. However, it’s possible to draw some broad conclusions. Firstly, the USSR embarked on the greatest experiment the world has ever known to draw peoples together across national boundaries for collective uplift. They eliminated the pogroms, allowed many languages to grow and bloom, put real resources behind promoting national cultures and made it a top national priority to place people from the formerly oppressed nations into positions of influence and power.

Secondly, they did this in the context of raising the living standards for the entire country far above what they had been in tsarist times, above every nation in the developing world, and achieved a rough parity with the most advanced nations on Earth with remarkable speed.

In that context, the inability of the Soviets to totally eliminate national antagonism has to be seen in a different light. Ultimately, how likely was it that they would succeed in that goal absent a broader transformation on a world level? Thousands of years of national oppression bound up in the material realities of capitalist development and feudal land ownership were never going to be unraveled in what, ultimately, was just a handful of decades in the historical sense.

Further, in the context of a massive campaign by the world’s most powerful nation to destroy the USSR, how is it possible that the USSR would not experience distortions imposed upon it for its own survival? That would also impact elements of policy from the social to the national.

Not just in nationalities policy, but in issues concerning everything from women’s rights to wages, Soviet policy backtracked from often pioneering (for the entire globe) policies to consolidate a greater sense of national unity around the socialist project or to solve practical problems with old methods when experimentation might risk losing more than would be gained.

The war in Ukraine further confirms just how tragic the Soviet collapse was, despite all its challenges and problems. The cultural-national pluralism of the Soviets has given way to the zero-sum agenda of the capitalist-oriented nationalists on all sides. These post-Soviet ruling classes have every reason to press claims (and not all without justification) that gain them territory, and ultimately the space to secure their profits in an actual commercial sense or as it concerns territorial integrity.

Twenty-seven million Soviets of all nationalities died in WWII. Despite the vigorous attempts by the Nazis to use nationality as an anti-communist weapon, they failed and multinational socialist unity powered the Soviet war machine to victory — a very fitting anti-racist funeral director to bury Nazism.

Socialist unity has collapsed into capitalist barbarism, which should not be a surprise. It is in fact what the genuine communist forces in the USSR always predicted would happen should the country collapse. Now more than ever it is important to remember the shining example of the Soviet Union in confronting hatred, bigotry and xenophobia, as we look for new paths to a more peaceful, sustainable and socialist future.

Sources

- William Mandel, Soviet But Not Russian: The ‘Other’ People’s of the Soviet Union (Ramparts Press, 1985) pp. 40-42

- https://www.sneps.net/t/images/Articles/Roeder_1991.pdf

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- William Mandel, Soviet But Not Russian: The ‘Other’ People’s of the Soviet Union (Ramparts Press, 1985) p. 133

- Ibid. p. 157

- Ibid. p. 160

- Ibid p. 108

- https://www.sneps.net/t/images/Articles/Roeder_1991.pdf

- Ibid

- https://www.marxists.org/history/ussr/overview/azerbaijan-land-in-bloom.pdf

- William Mandel, Soviet But Not Russian: The ‘Other’ People’s of the Soviet Union (Ramparts Press, 1985) p.18

- Ibid. pp. 22-23

- Terry Martin: Affirmative Action Empire: Nations and Nationalism in the Soviet Union, 1923–1939 (Cornell University Press, 2001) pp. 92-93

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1991_Soviet_Union_referendum

- https://news.gallup.com/poll/166538/former-soviet-countries-harm-breakup.aspx

- https://www.ucis.pitt.edu/nceeer/2005_818_09_McMann.pdf

- https://mobile.reuters.com/article/amp/idUSTRE7B713O20111208

- Ibid.