President Rodrigo Duterte of the Philippines declared martial law over the entire island of Mindanao May 23, allegedly responding to the violence of groups affiliated to the Islamic State in Marawi City. The timing, however, underscores a more ominous possibility: that the Duterte government is hunkering down for a widened military struggle should peace talks the National Democratic Front fail.

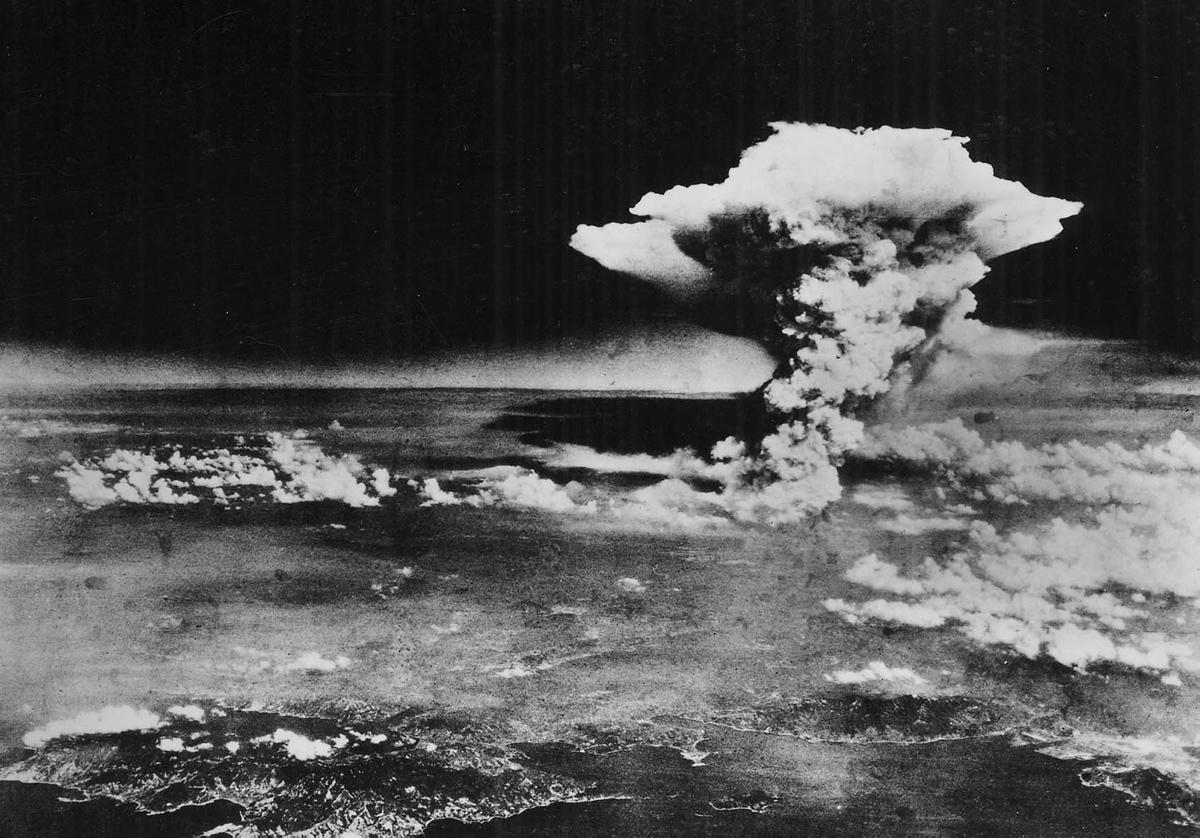

Upon the declaration of martial law, the Armed Forces of the Philippines began shelling, bombing and strafing parts of Marawi City, forcing thousands of civilians to flee.

Mindanao is one of the most materially rich regions in the Philippines, yet one of the poorest and is the site of an active and long-standing resistance movement by the oppressed Moro people, who are largely Muslim.

The Communist Party of the Philippines, which has a strong base in Mindanao as well, denounced the declaration of martial law as a disproportionate response that was harming civilians, as a cover for government military action against its New People’s Army and as a dangerous evocation of the Marcos period of nationwide martial law. The NPA initiated tactical offensives against the Philippines army, and the Duterte government canceled the fifth round of peace talks.

Duterte is now demanding that the Communist Party and NPA make a unilateral ceasefire and reverse course before the talks resume. The Communist Party has maintained for over two years of talks that a ceasefire would be impossible without social and economic reforms to address the country’s colonial underdevelopment and semi-feudal conditions, and has reaffirmed this point now that the government’s “cannons, bombs and heavy gunfire thunder against the people.”

Those peace talks saw some immediate breakthroughs when Duterte assumed the presidency last summer. Duterte himself is Mindanaoan, and as mayor of Davao City in the region for 22 years had developed a de facto working relationship with the National Democratic Movement there. But there still remains a possibility that the Duterte government will abandon the talks entirely and choose the same path as his predecessors of sharp and full-scale military assault.

The risk of the talks’ failure stems chiefly from the composition of the Duterte government: Like previous administrations, the military holds significant power and influence. It makes up some of the most backward-looking, reactionary elements in Filipino society and depends heavily on continued U.S. support and occupation.

Duterte’s ruling coalition has also been driving a vicious “war on drugs” in the Philippines, which to date has claimed up to 9,000 lives. Many of those killed were extra-judicial killings — vigilante actions that Duterte has praised. The “war on drugs,” like its counterpart in the United States, has focused primarily on the Philippines’ poorest communities who have turned to emigration and the underground market due to widespread landlessness, unemployment and low pay. As of 2012, for example, 19.2 percent of Filipinos lived in extreme poverty, making only about $1.25 per day.

These basic social and economic contradictions — held in place decade after decade by U.S. imperialism, military occupation and puppet governments — have been the driving factors of the nearly half-century civil war. If they are not addressed by the Duterte government, and if it chooses the continuation of martial law methods instead, the talks are likely to remain stalled — and the war will continue.