Anti-government protests in Belarus continue in the wake of the Aug 9 presidential election. Economic decline, coronavirus mismanagement and the government’s response to the protests have driven many Belarusians into the streets, including youth and industrial workers.

Pensioners joined the rallies over the weekend, calling for an end to President Alexander Lukashenko’s 26-year tenure and new elections.

The ruling Lukashenko administration has acceded to some demands of the protest movement. A constitutional reform will be held, followed by a new round of presidential elections. This has lessened some tensions in the country but strikes and protests are ongoing.

Although the protests’ stated target is Lukashenko, the real political aims of the leadership of the opposition is to bring Belarus into the U.S. and European Union sphere of influence.

The opposition’s self-appointed leaders openly call for privatization and foreign interference – policies that would immiserate the working class and relegate Belarus again to foreign domination.

Belarus and the restoration of capitalism

For much of its history Belarus suffered under foreign domination, first by the Lithuanian and Polish crown, and then the Russian Empire. With the 1917 Russian Revolution, Belarus became a sovereign, independent republic within the Soviet Union. During World War II, Belarus was invaded and occupied by Nazi Germany. Approximately 3 million Belarusians were killed by the Nazis during this time, out of a total of 27 million Soviet lives.

Despite all of these setbacks, through economic planning Soviet Belarus developed into an industrial center and the Soviet Union into a global power. Housing, education, health care and a job were guaranteed by the state.

The breakup of the Soviet Union and the restoration of capitalism in the early 1990s shattered the lives of workers: social spending was cut, health care privatized and schools defunded. The new “free market paradise” witnessed a surge in spousal abuse, child abuse, homelessness and environmental devastation.

“During 1991-1995, with the support of international organizations, Belarus initiated preliminary reforms toward transforming into a market economy,” according to the World Bank’s 2003 Belarus Country Brief.

In nearby Russia during this time, 75 to 85 percent of people lived below or just above the poverty line. A third of the population barely managed to survive from day to day. It was in this context that Lukashenko was elected president of Belarus in 1994, marking a reversal from the trend of privatization. The Belarusian state took control over most production, and much of the country’s GDP funded social programs and subsidies. “Market-oriented reforms were very limited,” the World Bank noted, meaning that that the capitalist measures destroying workers’ lives were held in check by the new Lukashenko administration.

Today, state-owned enterprises make up 70 percent of Belarus’ economy. The country’s social safety net is among the highest in the region. No domestic oligarchy has been allowed to form as in the case with other East European countries. Women retire at the age of 56, and men at the age of 61.

Belarus maintains a strong and important alliance with its neighbor Russia. Nearly half of Belarus’ foreign trade and almost all foreign direct investment is with Russia. In 1999 the two countries signed the Treaty on the Creation of a Union State of Russia and Belarus, which would create a confederation of the two former Soviet countries if fully implemented. For Russia, Belarus is a vital economic and geostrategic partner. Russian gas pipelines cross through Belarus en route to Western Europe. And Belarus provides a buffer near Russia’s own naval base in Kaliningrad, Russia’s westernmost territory.

Nationalist administration not without contradictions

Despite key assets being under state control, Belarus is still a capitalist society, and Lukashenko himself a contradictory figure. In recent years he has deepened cooperation with the West and sought to distance himself from Russia. He has even explored taking out IMF loans and privatizing state-owned enterprises, both long standing demands of the United States and European Union.

Secretary of State Mike Pompeo went to Belarus in February of this year. Pompeo’s trip to Minsk was the first visit by such a high-ranking U.S. official to the country in over 20 years. It was a major signal of openness towards the West and a willingness to fundamentally reorient Belarus’ foreign policy.

When Belarus entered recession in 2015, Lukashenko ordered the enterprises to cut costs by 25 percent and find trading partners other than Russia. Belinvestbank, the country’s largest bank, was marked for privatization under direction from a financial institution explicitly founded to privatize the former Eastern Bloc. As recently as November 2019, the Belarusian government affirmed their intent to privatize the bank.

Lukashenko has also at times emphasized or de-emphasized the Union Treaty with Russia based on political expediency. In 2017, the administration enacted 5-day visa waivers for citizens of the US and EU member states, among others. This created a considerable security risk for Russia, which shares an open border with Belarus. In response, Russia set up checkpoints into Belarus, and Lukashenko accused them of violating the Union Treaty.

And in what must have been taken as a grave diplomatic insult to Russia, Lukashenko even voiced approval of the U.S.-backed coup that toppled the Yanukovych government of Ukraine with the key participation of openly neo-Nazi elements in 2014.

Privatization and antagonism towards Russia are signals of willingness to open the economy to Western capital, and earned Lukashenko praise from imperialist powers. Slow concessions, however, are not enough for the United States and EU, who seek to completely privatize the state-owned enterprises under the guise of “modernisation”.

Domestic policy under Lukashenko can only be described as haphazard. Lukashenko dismissed the COVID-19 pandemic as “psychosis” and even suggested that the virus could be cured by drinking vodka or visiting a sauna. In the electoral realm, opposition figures who registered to run in the presidential race were arrested. And Lukashenko dismissed with sexist remarks women in the opposition who spoke against his government.

Personal callousness and economic decline could only alienate large swaths of the population. Many young people and industrial workers have joined in the movement against Lukashenko. But in the absence of a strong, progressive opposition, the pro-imperialist right wing has swooped in to fill the void.

Svyatana Tsikhanouskaya: The West’s appointed “president”

On Aug. 9, the Belarusian election commission reported that opposition leader Svyatana Tsikhanouskaya received 10 percent of the vote to Lukashenko’s 80 percent. Tsikhanouskaya alleged fraud, declaring herself the rightful winner. Even before the election, however, she made clear they never intended to respect the outcome. In an interview with Lenta.ru in July, Tsikhanouskaya was asked under what circumstances she would recognize Lukashenko’s victory. “I don’t consider this scenario at all,” she replied.

Early in her campaign, she attempted to portray herself as a political outsider, dodging questions on Belarus’ key alliance with Russia. When questioned about the Russian language’s official bilingual status, Tskihanouskaya, herself a Russian speaker, stated that this would be put up to vote. More than 70 percent of Belarusians speak Russian in their everyday lives. Demoting the Russian language in Belarus would be a significant gain for the right wing, who aim to decouple Belarusian society from its sister country Russia economically, diplomatically and culturally.

Tsikhanouskaya was asked under what circumstances she would recognize Lukashenko’s victory. “I don’t consider this scenario at all,” she replied.

Yet alongside the right wing’s recent gains, Tsikhanouskaya’s assumed political naïveté has dissipated. On Aug. 18 the opposition released a document listing the measures they would enact through 2030. Gone would be the Union Treaty and economic cooperation with Russia. Belarusian infrastructure would be sold off in such a way as to ensure their acquisition by the West. State oversight of mass media would be removed, enabling foreign capital to dominate the airwaves and political narrative. Russian broadcasting would be banned. And as if their aim could not be made more clear, the opposition program boldly includes potential applications for membership in the European Union and the NATO military alliance.

From exile in Lithuania, Tsikhanouskaya and the opposition have created what they call a coordination council, with the express purpose of removing Lukashenko from office and taking over the country. On Aug. 12, a member of Tsikanouskaya’s campaign staff published a video appeal openly calling for foreign intervention and for other countries to recognize Tsikanouskaya as the “only legally-elected President.”

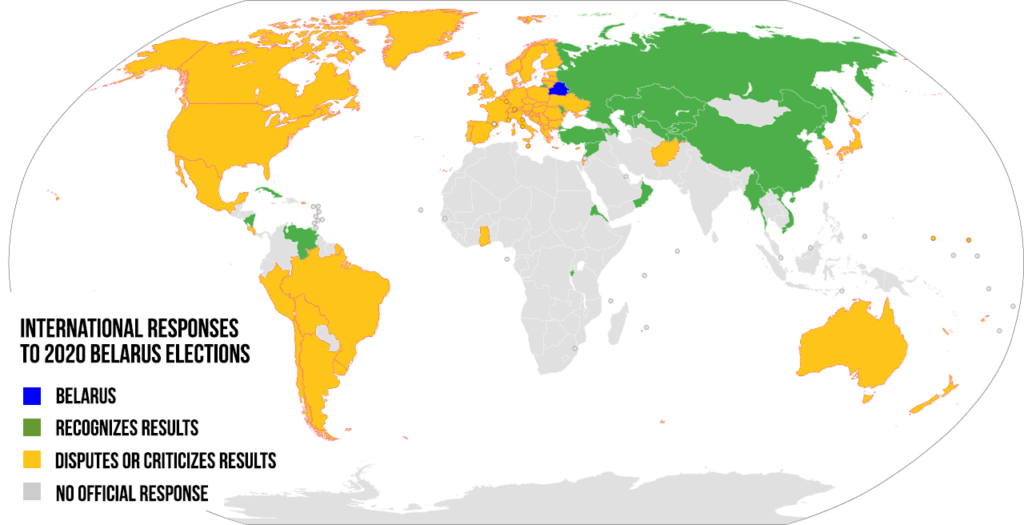

Lithuania accepted. On Aug. 18, the Lithuanian parliament, the Seimas, voted unanimously to not recognize the results of neighboring Belarus’ elections, going so far as to demand new presidential and parliamentary elections as well as sanctions on government officials. On Sept. 11, the Seimas passed a resolution declaring Lukashenko illegitimate, and Tsikanouskaya the “legally-elected leader of the Belarusian people.”

The real threat: imperialist domination

What happens in Belarus will resound globally. Militaristic think tank Defense One commented that the situation’s outcome “will reshape Russian and Western decision-making for years.” Russia’s westernmost oblast, Kaliningrad, is separated from Belarus by the 40 mile long Poland-Lithuania border, also known as the Suwalki Gap. Earlier this year, the U.S. simulated a war centered on the Suwalki Gap. This war exercise – with 29,000 U.S. soldiers, and 8,000 soldiers from 17 other countries – was the largest on European soil in the last 25 years.

Russia has reiterated its support for the Belarusian government, while calling on all nations to respect the sovereignty of Belarus and for a peaceful resolution. In an interview Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov stated: “No one hides the fact that it is about geopolitics, about the fight for the post-Soviet space. We have seen this fight earlier after the Soviet Union ceased to exist. The last example, of course, is Ukraine… It is all about geopolitics, about the very rules that our Western partners want to impose into everyday life on our continent and other parts of the world.”

Immediately after the protests began, the United States escalated. On Aug. 15, Pompeo declared his support for the opposition, saying the U.S. government would “help as best we can the Belarusian people [to] achieve sovereignty and freedom.” That same day Pompeo announced that the U.S. increased its number of soldiers in Poland to 5,000, with the option to increase to as many as 20,000 “if a threat justified it.” (BBC) Twenty-seven EU countries imposed new sanctions on Belarus for alleged human rights violations.

For the opposition, Sun. Aug 16 was to be a decisive anti-government march in Minsk, calling for an end to the “bloody regime.” Yet more than 65 thousand people from all over Belarus joined in a pro-government rally. The Communist Party of Belarus (KPB) has called on the Belarusian people “step back from the abyss.”

The Belarusian government for their part has engaged in dialogue with the protest movement and striking workers. Formal inquiries have been initiated into police brutality. Lukashenko personally visited a number of the major state-owned enterprises. The government has been replaced with new ministers, a handover that usually only happens after a new election. A call has been made for constitutional reform, to be followed by a new round of elections.

The symbol of the opposition is a red-and-white striped flag, first used by the right-wing government of 1918. Collaborationist, pro-Nazi elements of the Belarusian government under Nazi occupation also carried this flag in the 1930s. Later, the red and white would be raised by anticommunist emigrés against the Soviet Union. It was this symbol that formed the new government after the breakup of the Soviet Union, until it was replaced with Belarus’ current red and green flag, a modification of the Soviet flag.

People entering the streets in protest in Belarus have raised legitimate grievances, and many parts of the working class have entered into the struggle. Protestors are not in the streets demanding “privatize state-owned enterprises,” yet this is exactly what the right wing is pursuing with the backing of the U.S. ruling class. And most crucially, the political forces that have taken the leadership of the movement advocate Belarus’ entrance into the U.S.-led imperialist orbit.